On the Rocky Road to Globalization

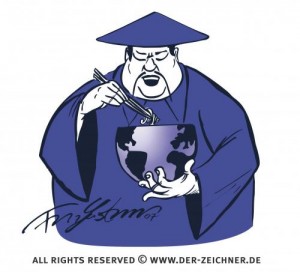

Kenneth Rogoff writes: What impact will China’s slowdown have on the red-hot contemporary art market? That might not seem like an obvious question, until one considers that, for emerging-market investors, art has become a critical tool for facilitating capital flight and hiding wealth. These investors have become a major factor in the art market’s spectacular price bubble of the last several years. So, with emerging market economies from Russia to Brazil mired in recession, will the bubble burst?

Just five months ago, Larry Fink, Chairman and CEO of BlackRock, the world’s largest asset manager, said that contemporary art has become one of the two most important stores of wealth internationally, along with apartments in major cities such as New York, London, and Vancouver. Forget gold as an inflation hedge; buy paintings.

Pablo Picasso’s “Women of Algiers” sold for $179 million at a Christie’s auction in New York, up from $32 million in 1997. Okay, it’s a Picasso. Yet it is not even the highest sale price paid this year. A Swiss collector reportedly paid close to $300 million in a private sale for Paul Gauguin’s 1892 “When Will You Marry?”

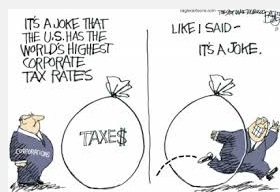

For economists, the art bubble raises many fascinating questions. Art is the last great unregulated investment opportunity.

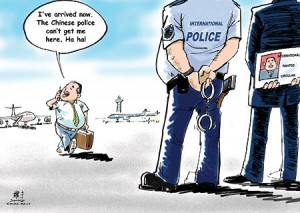

Doesn’t China have a regime of strict capital controls that limits citizens from taking more than $50,000 per year out of the country? Yes, but there are many ways of moving money in and out of China, including the time-honored method of “under and over invoicing.” Many estimates put capital flight from China at about $300 billion annually in recent years.

For example, to get money out of China, a Chinese seller might report a dollar value far below what she was actually paid by a cooperating Western importer, with the difference being deposited into an overseas bank account. It is extremely difficult to estimate capital flight. Identifying capital flight is akin to the old adage about blind men touching an elephant: It is difficult to describe, but you will recognize it when you see it.

The art may well be spirited off to a temperature- and humidity-controlled storage vault in Switzerland or Luxembourg. Reportedly, some art sales today result in paintings merely being moved from one section of a storage vault to another, recalling how the New York Federal Reserve registers gold sales between national central banks.

So how, then, will the emerging-market slowdown radiating from China affect contemporary art prices? In the short run, the answer is ambiguous, because more money is leaking out of the country even as the economy slows. In the long run, the outcome is pretty clear, especially if one throws in the coming Fed interest-rate hikes. With core buyers pulling back, and the opportunity cost rising, the end of the art bubble will not be a pretty picture.