Rocky Road to Globalization

Wall Street Journal editorial: Few privileges in the world are greater than U.S. citizenship, so why are a record number of Americans giving it up these days? The U.S. Treasury Department reported this week that 1,426 Americans turned in their passports between July and September, more than in any previous quarter. The total for the year is on pace to far exceed last year’s all-time-high of 3,415.

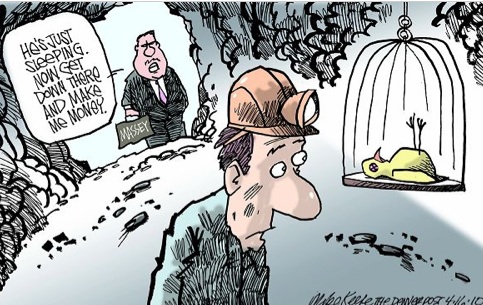

As recently as the George W. Bush years, only about 480 Americans renounced their citizenship annually. But in 2010 the Pelosi Congress and Barack Obama enacted the Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act, or Fatca. Aimed at tax evaders, the law has mostly made financial life hellish for law-abiding Americans living overseas, of whom there are some eight million.

Fatca requires that foreign banks, brokers, insurers and other financial institutions give the U.S. Internal Revenue Service detailed asset and transaction records for any accounts held by Americans, including corporate accounts controlled by American employees. If a firm fails to comply, the IRS can slap it with a 30% withholding tax on transactions originating in the U.S. Facing such risks and compliance costs, many foreign firms have decided it’s easier to dump their American clients.

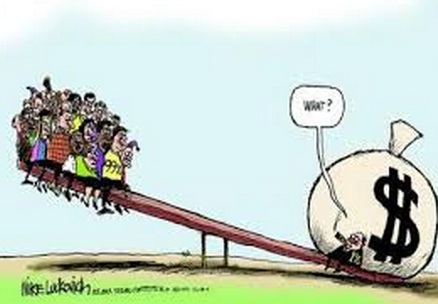

So Americans overseas are becoming increasingly unbankable. Not the wealthiest ones, of course, those “fat cat” potential tax evaders whom Democrats rail against. Much more vulnerable are sales reps, English teachers, lawyers, retirees—the overwhelming majority of American expatriates—whose modest finances make them unappealing clients amid Fatca’s compliance costs.

American expats in the Fatca age are also less attractive as employees and business partners, as any financial accounts they can access must now be exposed to government scrutiny—not only from the U.S. but potentially also from more than 100 other countries that have signed Fatca-related information-sharing agreements with Washington. Americans up for executive posts in Brazil, Singapore, Switzerland and elsewhere have been asked by their managers to renounce their U.S. citizenship or lose their promotion.

Little surprise, then, that renunciations are on the rise. A few thousand ex-Americans aren’t much of a political cause, but they’re a proxy for U.S. tax and regulatory policies that hamper the entire U.S. economy. For every American who renounces citizenship, there are many more foreigners refusing to do business with Yankee entrepreneurs or to invest money in U.S. businesses. That’s a problem for all Americans.