Anti-austerity backlash

Anti-austerity lawmakers forced Portugal’s center-right government to resign Tuesday by rejecting its policy proposals at the start of what was supposed to be a second consecutive term in office — and four more years of cutbacks and economic reforms.

The government’s dramatic collapse came less than two weeks after it was sworn in and raised questions about debt-heavy Portugal’s commitment to the fiscal discipline demanded of countries sharing the euro currency.

The moderate Socialist Party forged an unprecedented alliance with the Communist Party and the radical Left Bloc to get a 122-seat majority in the 230-seat Parliament, which it used to vote down the proposals. The defeat brought the government’s automatic resignation.

The government’s fall was also a political setback for the 19-nation eurozone’s austerity strategy. The policy of cutbacks was demanded by Germany and the others as a remedy for the bloc’s recent financial crisis.

Eurozone leaders had pointed to Portugal, and Ireland, as examples of how austerity paid off as their economies improved. Now, the progress Portugal made is in doubt, and some fear the country could go down the same road as Greece, which has needed three bailouts since 2010.

The triumph of the leftist alliance will likely give heart to anti-austerity forces in much bigger neighbor Spain, where a general election is scheduled for Dec. 20.

After four years in power the government lost its parliamentary majority in an Oct. 4 general election, which saw a public backlash against austerity measures adopted following an $84 billion bailout in 2011.

Socialist leader Antonio Costa is expected to become prime minister in coming weeks, supported by the Communists and Left Bloc.

Costa criticized the government for being “submissive” in its dealings with the rest of Europe and making more cutbacks than those demanded by the bailout creditors. “The Portuguese want change,” he said.

Outside Parliament, demonstrators at an anti-austerity protest by labor groups shouted “Victory!” as the news of the vote spread.

The leftist alliance intends to reverse cuts in pay, pensions and public services, as well as tax increases that have brought widespread hardship, street protests and strikes in recent years. Some 400,000 Portuguese left to seek work abroad.

Mario Centeno, the Socialist Party’s leading economic expert, sought to soothe eurozone and market fears about the next government’s plans, saying it would “abide by its European responsibilities and honor all its commitments.”

Centeno, who has a PhD in Economics from Harvard University and is a special adviser at the Bank of Portugal, is widely expected to be the country’s next finance minister.

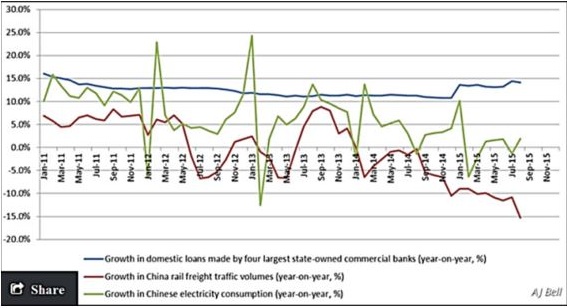

The current political upheaval has its roots in years of low growth and borrow-and-spend policies that weakened Portugal and compelled it to ask for the 2011 bailout amid the eurozone’s debt crisis.

Portugal’s budget deficit in 2010 was more than 10 percent but the European Union estimates it will be around 3 percent by the end of this year. Unemployment, which surged to a record 17 percent after the bailout, has fallen to 12 percent.

“Portugal today is incomparably better than it was four years ago,” outgoing Finance Minister Maria Luis Albuquerque told Parliament during the debate.

Among the measures planned by the leftist alliance are giving back government workers cut pay; unblocking pension increases; spending more on the national health service; providing free nursery schools for all 3-year-olds and free school books for all; reducing sales tax at restaurants from 23 percent to 13 percent; and restoring four public holidays that were scrapped to improve productivity.

The three parties in the alliance have in the past had hostile relations, however, and will be watched closely for any signs of friction.

The speaker of Parliament was due to inform President Anibal Cavaco Silva of the vote later Tuesday. The head of state, who has no executive power but oversees the government, will then consult the political parties in coming days before deciding whether to invite Costa to form a government. Cavaco Silva could choose to appoint a caretaker government, but analysts believe that is unlikely.