A Richmond Federal Reserve Report: Since the Federal Reserve’s founding, it has paid a regular dividend to banks that are Fed members in exchange for those banks holding stock in Federal Reserve Banks. Recent transportation legislation reduced these dividends and used the savings to help fund the bill. While this move provided a shortterm financing fix, it also raised a bigger question of whether banks will want to remain members of the Fed. Economic Brief

Author Archives: Adela Rogers

Cameron Fights for EU Relationship

Prime Minister David Cameron’s hopes to secure a reform deal on Britain’s relationship with the European Union.

A Number 10 source said the first session of the highly-anticipated European Council meeting had ended with a “significant gap on a number of issues”, including Cameron’s plans to obtain new safeguards for the City of London and a limit on welfare benefits for EU migrants.

EU leaders are also understood to be at odds over Cameron’s proposals to exempt Britain from the EU’s “ever closer union” commitment, as well as his desire for all 28 EU member states to sign up to a future treaty change.

Cameron told reporters earlier yesterday that he would be “battling for Britain” at the negotiating table.

“We’ve got some important work to do today and tomorrow and it’s going to be hard,” Cameron said, adding, “If we can get a good deal, I’ll take that deal. But I will not take a deal that doesn’t meet what we need.”

Cameron had hoped to hammer out a final agreement today, paving the way for an in/out vote on Britain’s EU membership as soon as 23 June. Yet last night’s gridlock raised questions about whether a deal – and a referendum – are likely to happen anytime soon.

Cameron has promised to hold the referendum by the end of 2017.

Bloomberg reported that Cameron had made a surprise bid to extend a so-called emergency brake on welfare payments to non-British citizens for a total of 13 years, nearly double the seven-year brake first proposed.

The PM told EU leaders that they had a make-or-break opportunity to “settle” the issue of Britain’s EU membership “for a generation”.

“The question of Britain’s place in Europe has been allowed to fester for too long and it is time to deal with it,” Cameron said.

Cameron is expected to hold multiple one-on-one meetings today in a last-ditch attempt to persuade other EU leaders to get behind his demands before the European Council meeting officially resumes later this morning.

The two-day meeting had been scheduled to wrap up around lunchtime, but EU officials warned last night that negotiations could last well into the weekend if an agreement cannot be reached.

Stop Bottling Himalayan Glacial Water

Brahma Chellaney writes: When identifying threats to Himalayan ecosystems, China stands out. For years, the People’s Republic has been engaged in frenzied damming of rivers and unbridled exploitation of mineral wealth on the resource-rich Tibetan Plateau. Now it is ramping up efforts to spur its bottled-water industry – the world’s largest and fastest-growing – to siphon off glacier water in the region.

Nearly three-quarters of the 18,000 high-altitude glaciers in the Great Himalayas are in Tibet, with the rest in India and its immediate neighborhood. The Tibetan glaciers, along with numerous mountain springs and lakes, supply water to Asia’s great rivers, from the Mekong and the Yangtze to the Indus and the Yellow. In fact, the Tibetan Plateau is the starting point of almost all of Asia’s major river systems.

By annexing Tibet, China thus changed Asia’s water map. And it is aiming to change it further, as it builds dams that redirect trans-boundary riparian flows, thereby acquiring significant leverage over downriver countries.

But China is not motivated purely by strategic considerations. With much of the water in its rivers, lakes, and aquifers unfit for human consumption, pristine water has become the new oil for China – a precious and vital resource, the overexploitation of which risks wrecking the natural environment.

China seems to think that the bottling of Himalayan glacier water can serve as a new engine of growth, powered by government subsidies. As part of the official “Share Tibet’s Good Water with the World” campaign, China is offering bottlers incentives like tax breaks, low-interest loans, and a tiny extraction fee of just CN¥3 ($0.45) per cubic meter (or 1,000 liters).

Some 30 companies have already been awarded licenses to bottle water from Tibet’s ice-capped peaks.

Ominously, the Chinese bottled-water industry is sourcing its glacier water mainly from the eastern Himalayas, where accelerated melting of snow and ice fields is already raising concerns in the international scientific community.

One of the world’s most bio-diverse but ecologically fragile regions, the Tibetan Plateau is now warming at more than twice the average global rate. Beyond undermining the pivotal role Tibet plays in Asian hydrology and climate, this trend endangers the Tibetan Plateau’s unique bird, mammal, amphibian, reptile, fish, and medicinal-plant species.

Nonetheless, China is not reconsidering its unbridled extraction of Tibet’s resources. On the contrary, since building railways to Tibet – the first was completed in 2006, with an extension opened in 2014 – China’s efforts have gone into overdrive.

Beyond water, Tibet is the world’s top lithium producer; home to China’s largest reserves of several metals, including copper and chromite (used in steel production); and an important source of diamonds, gold, and uranium.

China is forcing a growing number of people and ecosystems to pay the price for its imprudent approach to economic growth.

Glacier-water mining has major environmental costs in terms of biodiversity loss, impairment of some ecosystem services due to insufficient runoff water, and potential depletion or degradation of glacial springs. Moreover, the process of sourcing, processing, bottling, and transporting glacial water from the Himalayas to Chinese cities thousands of miles away has a very large carbon footprint.

Bottling glacier water is not the right way to quench China’s thirst.

How Can Africa Overcome Downturn in Commodity Prices?

Kingsley Chiedu Moghalu writes: The global commodity slump and China’s economic slowdown have pummeled several African economies, making clear that the continent’s “rise” was a myth. Now is the time to re-examine the basis of Africa’s recent “boom” and move from feel-good rhetoric to action that will drive genuine economic transformation.

Commodity exporters such as Angola, Ghana, Nigeria, South Africa, and Zambia are reeling, with their currencies crashing since the prices of commodities such as oil and copper began falling sharply.

The heart of the matter is this: African countries mistook a commodity supercycle-fed boom for a sustainable economic transformation.

Africa benefited from higher GDP growth and expanded opportunity over the last decade. But hundreds of millions of Africans have yet to be lifted out of poverty in the manner China has accomplished – a path that other Asian countries, such as India and Vietnam, are following as well.

Without question, many individual Africans have become stupendously wealthy and are playing more assertive roles in the world of business. Entrepreneurship is on the rise, especially among young Africans, gradually replacing the dead end of foreign aid. But the vast majority of Africans lag far behind.

Despite the spread of formal democracy on the continent, the nature of domestic politics in most African countries has hardly changed. Real leadership involves not just mobilizing citizens to vote for candidates, but also effective management, strategy, and execution of public policy. And yet power often is sought for its own sake or to secure control of state resources on behalf of ethnic kin or co-religionists. Politics is not yet, as it ought to be, a contest of ideas and programs affecting all citizens. Corruption thrives in such an environment.

Moreover, a proper understanding of economics is necessary. The continent and its leaders have so far failed to understand – or, where they have understood, to apply – historical lessons concerning how the wealth of nations is created. Instead, we often see uncritical acceptance of the received but self-interested conventional wisdom of globalization.

Achieving prosperity in the overarching context of globalization requires creating a competitive economy based on value-added production and export. But it also requires selective engagement with international treaties that favor today’s competitive good producers but put at a disadvantage the developing countries that are increasingly the markets for these goods.

This is precisely why Africa’s biggest folly is to believe that mineral resources and other raw commodities are automatically a source of wealth.

Africa’s future competitiveness and prosperity lie in the opportunities afforded by science, technology, and innovation.

Africa’s leaders in the public and private sectors have an opportunity to clear the policy bottlenecks that have prevented the commercialization of African inventions, especially in large economies such as Nigeria, South Africa (which has a more advanced innovation policy than the rest of the continent), and Kenya. Innovation must be deployed to cost-effective, competitive manufacturing and service industries.

Is it Time for a Carbon Tax?

Kemal Dervis and Karim Foda write: Over the last few decades, oil prices have fluctuated widely – ranging from $10 to $140 a barrel – posing a challenge to producers and consumers alike. For policymakers, however, these fluctuations present an opportunity to advance the key global objectives – reflected in the Sustainable Development Goals adopted last September and the climate agreement reached in Paris in December – of mitigating climate change and building a more sustainable economy.

Recent oil-price fluctuations resemble the classic cobweb model of microeconomic theory. High prices spur increased investment in oil. But, given long lags between exploration and exploitation, by the time the new output capacity actually comes on stream, substitution has already taken place, and demand often no longer justifies the available supply. At that point, prices fall, and exploration and investment decline as well, including for oil substitutes. When new shortages develop, prices begin rising again, and the cycle repeats.

The cycle will continue, though other factors – such as the steadily declining costs of renewable energy and the shift toward less energy-intensive production processes – mean that it will probably spin within a lower range. In any case, a price increase is inevitable.

Against this background, today’s very low prices – below $35 a barrel at times since the beginning of this year – create a golden opportunity (which one of the authors has been recommending for over a year) to implement a variable carbon tax. The idea is simple: The tax would decrease gradually as oil prices rise, and then increase again when prices eventually come back down.

If the adjustments are asymmetric – larger increases when prices fall, and smaller decreases when prices rise – this system would gradually raise the overall carbon tax, even as it follows a counter-cyclical pattern. Such an incremental increase is what most models for controlling climate change call for.

Consider this scenario. Imagine that in December 2014, policymakers introduced a tax of $100 per metric ton of carbon (equivalent to a $27 tax on CO2). For American consumers, the immediate impact of this new tax – assuming its costs were passed fully onto consumers – would have been a $0.24 increase in the average national price of a gallon of gasoline, from $2.23 to $2.47, still far below the highs of 2007 and 2008.

If, since then, each $5 increase in the oil price brought a $30 per ton decrease in the carbon tax, and each $5 decline brought a $45-per-ton increase, the result would be a $0.91 difference between the standard market price and the actual tax-inclusive consumer price last month [see figure]. That increase would have raised the carbon price substantially, providing governments with revenue – reaching $375 per ton of carbon today – to apply to meeting fiscal priorities, all while cushioning the fall in gasoline prices caused by the steep decline in the price of crude. While $375 per ton is a very high price, reflecting the particularly low price of oil today, even a lower carbon price – in the range of $150-250 per ton – would be sufficient to meet international climate goals over the next decade.

With this approach, policymakers could use the market to help propel their economies away from dependence on fossil fuels, redistributing producer surplus (profits) from oil producers to the treasuries of importing countries, without placing too large or sudden a burden on consumers. In fact, by stabilizing user costs, it would offer significant gains.

The key to this strategy’s political feasibility is to launch it while prices are very low. Once it is in place, it will become a little-noticed, politically uncontroversial part of pricing for gasoline (and other products) – one that produces far-reaching benefits. Some of the revenue could be returned to the public in the form of tax cuts or research support.

Despite the obvious benefits of a variable carbon tax, no country has capitalized on today’s low oil prices to raise carbon prices in this or a similar form, though US President Barack Obama’s call for a tax on oil suggests that he recognizes the opening low prices represent. This should change. The opportunity to implement a policy that is simultaneously sensible, flexible, gentle, and effective in advancing national and global goals does not arise very often. Policymakers must seize it when it does. The time for a variable stabilizing carbon tax is now.

Is an Anglosphere Viable?

Gareth Evans writes: One of the most bizarre arguments made by the people who support Britain’s exit from the European Union is the notion that a self-exiled UK will find a new global relevance, and indeed leadership role, as the center of the “Anglosphere.”

The idea is that there are a group of countries – with the “Five Eyes” intelligence-sharing community of the US, UK, Australia, Canada and New Zealand at its core – who share so much of a common heritage that they can be a new, united force for global peace and prosperity.

Geostrategically, the main game is, as it has been for most of recorded time, geography rather than history, and the biggest game of all for the foreseeable future is the emerging contest for global supremacy between the US and China.

The US does value highly its relationship with NATO members Britain and Canada. Yet it is hard to see US leaders devoting time and energy to attending Commonwealth Heads of Government meetings, which is essentially what any formal Anglosphere structure would amount to.

Australia, for its part, sees its security future as wholly bound up in the Indo-Pacific region. Anglosphere connections mattered a lot for Australians and others in the days before the UK joined the European Common Market. The severance of those ties was painful for our dairy and other industries, but for Britain hard-headed self-interest understandably prevailed. Self-interest now prevails for the rest of us.

In Australia’s case, our trade future is bound up either with all-embracing global agreements, or at least substantial regional ones like the Trans-Pacific Partnership, with the US the key player, or the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership now being negotiated between ASEAN and Australia, China, India, Japan, South Korea and New Zealand.

The US manifestly feels the same way.

Probably the hardest truth that Britain’s Anglosphere dreamers must confront is that there is just no mood politically to build some new global association of the linguistically and culturally righteous.

While many of us living in the so-called Anglosphere remain nostalgic about Britain. The truth of the matter is that if Britain steps away from Europe, thinking it can compensate by creating an influential new international grouping of its own, it will find itself very lonely indeed.

Morocco Backs Renewable Energy

Moha Ennaji writes: Morocco’s drive to become a regional renewable-energy powerhouse offers a real option for economic development in other Arab countries.

Morocco has been investing in large-scale renewable-energy projects for some time; but only now are these investments coming online. Perhaps the most impressive is the gigantic Noor-1 solar-energy compound, located in the Moroccan desert near Ouarzazate. Opened on February 4, Noor-1 uses highly advanced technology to store energy for use at night and on cloudy days.

Considered the largest solar power plant in the world, Noor-1 is expected to produce enough energy for more than a million people, with extra power eventually to be exported to Europe and Africa, according to the World Bank. Given that Morocco imports around 97% of its energy supply, and possesses no oil or natural gas deposits of its own, the government has viewed developing renewable energy as the only way to ensure the country’s continuing economic development. This is an insight others in the region should heed.

The Noor-1 project, covering an area of more than 4.5 square kilometers (1.7 square miles) with 500,000 curved mirrors – some as high as 12 meters – cost around $700 million. But it is intended to be only one part of a huge solar compound extending over 30 square kilometers. Indeed, by 2018, three more plants, Noor-II, Noor-III, and Noor-Midelt will be constructed, using a combination of technologies, including thermosolar and photovoltaic. The project will generate up to 2,000 megawatts daily by 2020, helping to reduce the development gap between urban and rural areas.

Of course, the project has demanded huge sums in investment. Of the $9 billion project’s financing, some $1 billion has come from a German investment bank, $400 million from the World Bank, and $596 million from the European Investment Bank. The rest of the funding has come from Morocco’s government as part of its national development strategy.

In the near future, Morocco will also develop a wind program with a capacity of at least 2,000 MW daily, and a 2,000 MW hydropower project. These could provide the country with 42% of its total electricity production. This represents an unparalleled proportion of renewable energy at both the regional and the international levels.

Already, the Tarfaya Wind Farm, positioned on Morocco’s Southern Atlantic Coast, is Africa’s biggest. With 131 turbines and a daily capacity of more than 300 MW, Tarfaya will help reduce Morocco’s carbon dioxide emissions by 900,000 tons annually, and cut the country’s annual oil import bill by more than $190 million.

Morocco’s government is convinced that reform and development will confirm its emergence as a regional leader and gateway to Africa.

Investors are aware of Morocco’s exceptional geographic position and its political stability in a region all too often held back by uncertainty. The country’s giant solar complex and other investments will help boost the country’s energy independence, reduce costs, and expand access to power. Others in Africa and the Middle East should take note.

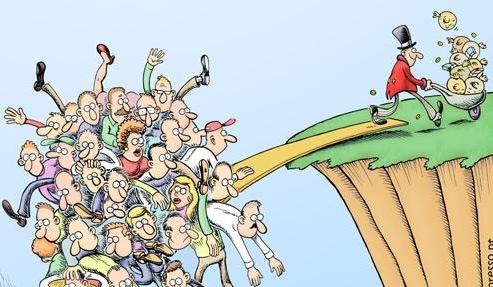

Does the Inequality Index Impact on Peoples’ Lives?

Dumbisa Moya writes: Over the past decade, income inequality has come to be ranked alongside terrorism, climate change, pandemics, and economic stagnation as one of the most urgent issues on the international policy agenda. And yet, despite all the attention, few potentially effective solutions have been proposed. Identifying the best policies for reducing inequality remains a puzzle.

To understand why the problem confounds policymakers, it is helpful to compare the world’s two largest economies. The United States is a liberal democracy with a market-based economy, in which the factors of production are privately owned. China, by contrast, is governed by a political class that holds democracy in contempt. Its economy – despite decades of pro-market reforms – continues to be defined by heavy state intervention.

But despite their radically different political and economic systems, the two countries have roughly the same level of income inequality. Each country’s Gini coefficient – the most commonly used measure of income equality – is roughly 0.47.

In one important way, however, their situations are very different. In the US, inequality is rapidly worsening. During the same period, inequality in China has been declining.

This poses a challenge for policymakers. Free market capitalism has proved itself to be the best system for driving income growth and creating a large economic surplus. And yet, when it comes to the distribution of income, it performs far less well.

Most democratic societies have attempted to address the problem through left-leaning redistributive policies or right-leaning supply-side approaches.

Adding to the challenges of the policy debate are assertions that inequality is unimportant. If a rising tide is lifting all boats, the thinking goes, it doesn’t matter that some may be rising more slowly than others.

Those who argue for de-emphasizing income inequality maintain that public policy should seek to ensure that all citizens enjoy basic living standards – nutritious food, adequate shelter, quality health care, and modern infrastructure – rather than aiming to narrow the gap between rich and poor. Indeed, some contend that income inequality drives economic growth and that redistributive transfers weaken the incentive to work, in turn depressing productivity, reducing investment, and ultimately harming the wider community.

But societies do not flourish on economic growth alone. They suffer when the poor are unable to see a path toward betterment. Social mobility in the US (and elsewhere) has been declining, undermining faith in the “American Dream.”

Over the past 50 years, as countries such as China and India posted double-digit economic growth, the global Gini coefficient dropped from 0.65 to 0.55. But further headway is unlikely – at least for the foreseeable future.

Economic growth in most emerging economies has slowed below 7%, the threshold needed to double per capita income in a single generation. In many countries, the rate has fallen below the point at which it is likely to make a significant dent in poverty.

This bleak economic outlook has serious consequences. Widening inequality provides fodder for political unrest, as citizens watch their prospects decline.

Globally, the slowdown in economic convergence has similar implications, as richer countries maintain their outsize influence around the world – leading to disaffection and radicalization among the poor. As difficult a puzzle as income inequality may seem today, failing to solve it could lead to far more severe challenges.

Can Capital Flows Be Stabilized?

Joseph E. Stiglitz and Hamid Rashid write: Developing countries are bracing for a major slowdown this year. According to the UN report World Economic Situation and Prospects 2016, their growth averaged only 3.8% in 2015 – the lowest rate since the global financial crisis in 2009 and matched in this century only by the recessionary year of 2001. And what is important to bear in mind is that the slowdown in China and the deep recessions in the Russian Federation and Brazil only explain part of the broad falloff in growth.

True, falling demand for natural resources in China (which accounts for nearly half of global demand for base metals) has had a lot to do with the sharp declines in these prices, which have hit many developing and emerging economies in Latin America and Africa hard. Indeed, the UN report lists 29 economies that are likely to be badly affected by China’s slowdown. And the collapse of oil prices by more than 60% since July 2014 has undermined the growth prospects of oil exporters.

The real worry, however, is not just falling commodity prices, but also massive capital outflows. During 2009-2014, developing countries collectively received a net capital inflow of $2.2 trillion, partly owing to quantitative easing in advanced economies, which pushed interest rates there to near zero.

The search for higher yields drove investors and speculators to developing countries, where the inflows increased leverage, propped up equity prices, and in some cases supported a commodity price boom.

But the capital flows are now reversing, turning negative for the first time since 2006, with net outflows from developing countries in 2015 exceeding $600 billion – more than one-quarter of the inflows they received during the previous six years.

This is not the first time that developing countries have faced the challenges of managing pro-cyclical hot capital, but the magnitudes this time are overwhelming.

Of course, the East Asian economies today are better able to withstand such massive outflows, given their accumulation of international reserves since the financial crisis in 1997.

The stockpile of reserves may partly explain why huge outflows have not triggered a full-blown financial crisis in developing countries. But not all countries are so fortunate to have a large arsenal.

Once again, advocates of free mobility for destabilizing short-term capital flows are being proven wrong. Many emerging markets recognized the dangers and tried to reduce capital inflows. South Korea, for example, has been using a series of macro-prudential measures since 2010, aimed at moderating pro-cyclical cross-border banking-sector liabilities. The measures taken were only partially successful, as the data above show. The question is, what should they do now?

Corporate sectors in developing countries, having increased their leverage with capital inflows during the post-2008 period, are particularly vulnerable.

Governments need to take quick action to avoid becoming liable for exposures. Expedited debtor-friendly bankruptcy procedures could ensure quick restructuring and provide a framework for renegotiating debts.

Developing-country governments should also encourage the conversion of such debts to GDP-linked or other types of indexed bonds.

While reserves may provide some cushion for minimizing the adverse effects of capital outflows, in most cases they will not be sufficient.

In some cases, it may be necessary to introduce selective, targeted, and time-bound capital controls to stem outflows, especially outflows through banking channels. This is perhaps the only recourse for many developing countries to avoid a catastrophic financial crisis. It is important that they act soon.

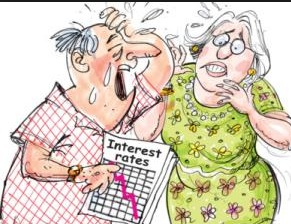

Do Negative Interest Rates Increase Financial Instabilty?

Stephen S. Rach writes: In what could well be a final act of desperation, central banks are abdicating effective control of the economies they have been entrusted to manage. First came zero interest rates, then quantitative easing, and now negative interest rates – one futile attempt begetting another. Just as the first two gambits failed to gain meaningful economic traction in chronically weak recoveries, the shift to negative rates will only compound the risks of financial instability and set the stage for the next crisis.

The adoption of negative interest rates – initially launched in Europe in 2014 and now embraced in Japan – represents a major turning point for central banking. Previously, emphasis had been placed on boosting aggregate demand – primarily by lowering the cost of borrowing, but also by spurring wealth effects from appreciating financial assets. But now, by imposing penalties on excess reserves left on deposit with central banks, negative interest rates drive stimulus through the supply side of the credit equation – in effect, urging banks to make new loans regardless of the demand for such funds.

This misses the essence of what is ailing a post-crisis world. As Nomura economist Richard Koo has argued about Japan, the focus should be on the demand side of crisis-battered economies, where growth is impaired by a debt-rejection syndrome that invariably takes hold in the aftermath of a “balance sheet recession.”

Such impairment is global in scope. It’s not just Japan, where the purportedly powerful impetus of Abenomics has failed to dislodge a struggling economy from 24 years of 0.8% inflation-adjusted GDP growth. It’s also the US, where consumer demand – the epicenter of America’s Great Recession – remains stuck in an eight-year quagmire of just 1.5% average real growth. Even worse is the eurozone, where real GDP growth has averaged just 0.1% over the 2008-2015 period.

All of this speaks to the impotence of central banks to jump-start aggregate demand in balance-sheet-constrained economies that have fallen into 1930s-style “liquidity traps.”

This could be the greatest failure of modern central banking. Yet denial runs deep. Former Federal Reserve Chair Alan Greenspan’s “mission accomplished” speech in early 2004 is an important case in point. Greenspan took credit for using super-easy monetary policy to clean up the mess after the dot-com bubble burst in 2000, while insisting that the Fed should feel vindicated for not leaning against the speculative madness of the late 1990s.

That left Greenspan’s successor on a very slippery slope.

European Central Bank President Mario Draghi’s famous 2012 promise to do “whatever it takes” to defend the euro took the ECB down the same path – first zero interest rates, then quantitative easing, now negative policy rates.

Most major central banks are clinging to the false belief that there is no difference between the efficacy of the conventional tactics of monetary policy and unconventional tools such as quantitative easing and negative interest rates.

Therein lies the problem. In the era of conventional monetary policy, transmission channels were largely confined to borrowing costs and their associated impacts on credit-sensitive sectors of real economies, such as homebuilding, motor vehicles, and business capital spending.

As those sectors rose and fell in response to shifts in benchmark interest rates, repercussions throughout the system (so-called multiplier effects) were often reinforced by real and psychological gains in asset markets (wealth effects).

Two serious complications have arisen from this approach. The first is that central banks have ignored the risks of financial instability.

Second, politicians, drawing false comfort from frothy asset markets, were less inclined to opt for fiscal stimulus – effectively closing off the only realistic escape route from a liquidity trap.

The shift to negative interest rates is all the more problematic. Given persistent sluggish aggregate demand worldwide, a new set of risks is introduced by penalizing banks for not making new loans. This is the functional equivalent of promoting another surge of “zombie lending” – the uneconomic loans made to insolvent Japanese borrowers in the 1990s. Central banking, having lost its way, is in crisis. Can the world economy be far behind?