Still a teacher at heart, U.S. Sen. Elizabeth Warren moved smoothly through her “America’s Agenda” program. The senator talked about her family’s meager resources as she was growing up. She spoke of how her mother, after her father suffered a heart attack, “put on lipstick, squared her shoulders and walked over to Sears and got a minimum wage job,” thus saving the family station wagon and their home.

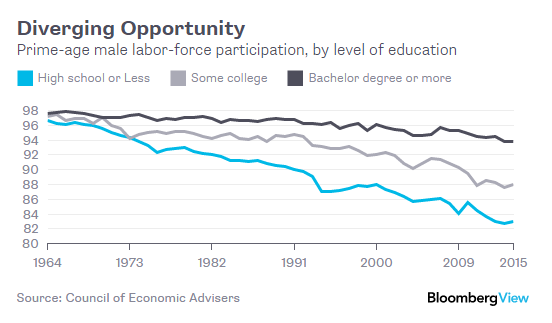

She said one in three people who have a credit file are in collection, suggesting the loss of a strong middle class, and she knows why that’s happened. From 1935 to 1980 … all the new income was divided … and 90 percent went to us … so what went wrong?

She described how problems began with Reagan and trickle-down economics, which she said helped the “rich and powerful become wealthy” in the hope that their wealth would flow down to the middle class. And then when the whole thing fell apart, as it was bound to do in 2008,” the taxpayers suffered, she said, “There are still remaining loopholes that need to be closed, and suggested that closing just one – allowing “giant corporations” to receive tax deductions for bonuses they pay out – would save $55 billion over a decade. That money could be used to refinance all student loans, replace every water pipe in Flint, Michigan, and more than 60 other cities, and give raises to every person on Social Security or on disability and to veterans. Organizers said about 100 people were turned away from Wednesday’s event when the room was filled but were allowed to stand in a hallway, where they could hear the speech and were offered an opportunity to take a photograph with Ms. Warren when the event ended.

Meeting with reporters, Ms. Warren said she is extremely concerned about the “growing threat of Zika.”The Democrats have been pushing the Republicans to do adequate funding on the research and to make sure the public health associations have the money they need to deal with mosquito control,” she said, adding that she felt she and other senators should be in Washington voting more money for that purpose.