Harold James writes: So far, the Volkswagen scandal has played out according to a well-worn script. Revelations of disgraceful corporate behavior emerge (in this case, the German automaker’s programming of 11 million diesel vehicles to turn on their engines’ pollution-control systems only when undergoing emissions testing). Executives apologize. Some lose their jobs. Their successors promise to change the corporate culture. Governments prepare to levy enormous fines. Life goes on.

This scenario has become a familiar one, particularly since the 2008 financial crisis. Banks and other financial institutions have enacted it repeatedly, even as successive scandals continued to erode confidence in the entire industry. Those cases, together with Volkswagen’s “clean diesel” scam, should give us cause to rethink our approach to corporate malfeasance.

Promises of better behavior are clearly not enough, as the seemingly endless number of scandals in the financial industry has shown. As soon as regulators had dealt with one case of market manipulation, another emerged.

The trouble with the banking industry is that it is built on a principle that creates incentives for bad behavior. Banks know more about market conditions (and the likelihood of their loans being repaid) than their depositors do. This secrecy lies at the heart of financial activity. Polite analysts call it “management of information.” Critics consider it a form of insider dealing.

Banks are also uniquely vulnerable to scandal because many of their employees are simultaneously behaving in ways that could influence the reputation, and even the balance sheet, of the entire firm. In the 1990s, a single Singapore-based trader brought down the venerable Barings Bank. In 2004, Citigroup’s Japanese private bank was shut down after a trader rigged the government bond market. At JPMorgan Chase, a single trader – known as “the London Whale” – cost the company $6.2 billion.

What these repeated scandals show is that apologies are little more than words, and that talk about changing the corporate culture is usually meaningless. As long as the incentives remain the same, so will the culture.

The Volkswagen case is a useful reminder that corporate wrongdoing is not confined to the banking industry. There were incentives in the automobile industry to game the system. Everyone knows that actual fuel economy does not correspond to the numbers on the showroom sticker, which are generated by tests carried out with the wind blowing from behind or on a particularly smooth road surface. Anyone who has stood next to a diesel vehicle could tell that it was smellier than cars powered by gasoline.

There are two important similarities between the scandals in the finance industry and at Volkswagen. The first is that large corporations, whether banks or manufacturers, are deeply embedded in national politics, with elected officials dependent on such firms for job creation and tax revenues.

The second similarity is that both industries are subject to multiple regulatory objectives. Regulators may want banks to be safer, but they also want them to lend more to the real economy.

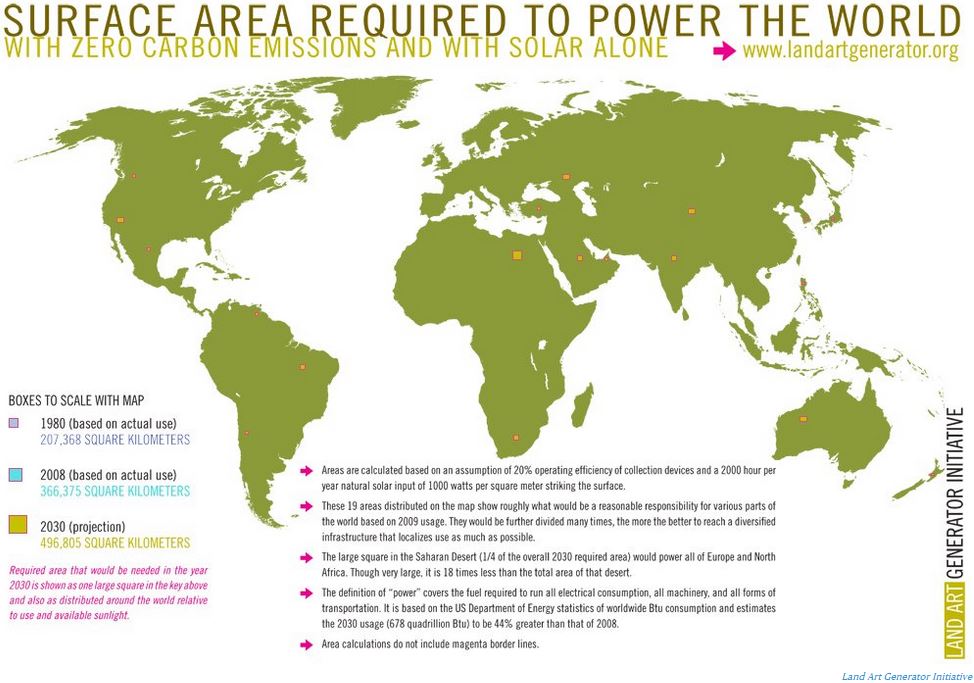

The regulation of automobile emissions faces a similar problem. As regulators’ focus turned toward limiting global warming, there were tremendous incentives to manufacture vehicles that produced fewer greenhouse-gas emissions,

As the Volkswagen crisis so vividly illustrates, we need more than corporate apology and regulatory wrist slapping. It is time for a sustained discussion about how to craft regulations that provide the proper incentives to achieve the objectives we truly desire: economic and social wellbeing. It is only when that discussion takes place that we will get the banks, cars, and other goods and services that we want.