Thomas Biesheuvel, Eddie van der Walt and Jesse Riseborough write: Ivan Glasenberg is running out of luck. The South African-born accountant, whose Glencore Plc rode the China-fueled boom in commodities the past 10 years like no one else, is emerging as the most prominent casualty of the bust.

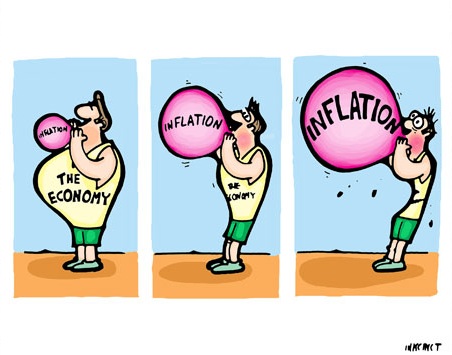

The descent has been so swift that many investors are now wondering where it will end. As Glencore’s share price plunged by almost a third, bringing its losses since March to 76 percent, the credit markets registered mounting worries about its debt load: Its bonds tumbled and derivatives traders started demanding upfront payments to protect against a default by the company, the first time that’s happened since 2009.

While traders were at a loss to identify the catalyst for Monday’s rout, the underlying reasons have remained constant: commodity prices are too low, Glencore’s debt is too high and growth in China, the engine that drove prices for everything from copper to coal to oil is the weakest it’s been in a quarter century.

In recent weeks, Glencore has sought to reassure investors by promising to prepare its finances for any doomsday scenario.

At its height in 2014, Glencore was worth more than $85 billion after its $29 billion all-share takeover of Xstrata Plc, then the world’s biggest coal exporter. Even as recently as August 2014, Glasenberg made an approach to buy Rio Tinto Group, the second-biggest miner. That was rebuffed. As of Monday in London, Rio’s market capitalization was $59 billion, almost four times Glencore’s.

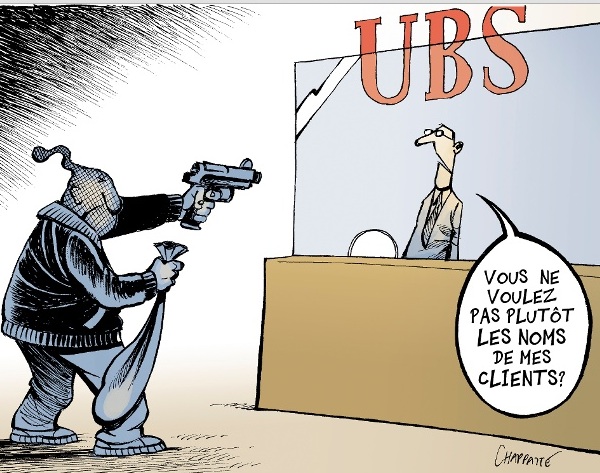

Glencore, based in Zug, Switzerland, trades everything from wheat to oil to cobalt. It’s the world’s biggest exporter of power-station coal, with more than 30 mines in Australia, Colombia and South Africa and is among the top three agricultural exporters in Russia, the European Union, Canada and Australia. The company controls more than 150 mining and metallurgical, oil production and agricultural assets and employs about 180,000 people.

For all that, Investec Plc, an investment bank, said Monday that there would be little left for shareholders should low prices persist. Goldman Sachs Group Inc. said last week that Glencore’s steps to reduce debt and bolster its balance sheet were inadequate.

Glasenberg, a former coal trader, honed his skills over more than 30 years in the commodity trading business since he joined a predecessor firm, Marc Rich & Co., in 1984. He was part of a $1.2 billion management buyout from Rich in 1994, which saw the company renamed Glencore. The 2011 IPO made him a billionaire on paper with his stake worth almost $10 billion.

Glasenberg has also been one of the industry’s most outspoken figures, railing against rivals for oversupplying the market and saying fellow executives had “screwed up” by

building too many mines. He has also taken the lead on trying to remedy the problem, cutting output at its Australian coal mines and saying last month that it would close copper mines in the Democratic Republic of Congo and Zambia that account for about 2.2 percent of global supply.

Glencore’s rivals haven’t been left unscathed. In London trading, BHP Billiton Ltd., the world’s biggest mining company, has fallen 26 percent this year, while Rio Tinto has declined 30 percent. Anglo American Plc, which like Glencore is highly leveraged, has slumped 53 percent. The Bloomberg World Mining Index of producers has shed 32 percent this year.

Glencore announced a debt-cutting program earlier this month in an attempt to reduce the company’s borrowings to $20 billion from $30 billion. The company has also has hired Citigroup Inc. and Credit Suisse Group AG to sell a minority stake in its agricultural business, a person familiar with the situation said Friday.