Complaints from the IMF/World Bank meetings in Peru.

Nick Asheshov writes: The IMF/World Bank AGM meetings were deeply confused. The muddle came not from the third world, the usual suspects, much less from Peru, but from the IMF itself together with the big shot central banks, led by the Fed in Washington, The European Central Bank in Frankfurt, the Bank of England and their equivalents in China and Japan.

It quickly became clear that the international financial system, which is run by the directors and staff of the Fund, is not only dangerously unstable but that there is worse to come. The world economy, said Christine Lagarde, the Fund’s managing director, is barely growing, at only 3.1% — Fundspeak for 2.3%.

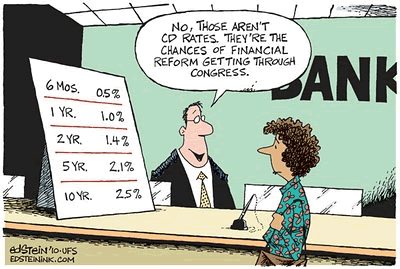

Mme. Lagarde could have added that economic growth is not actually her job. Her job, the task of the International Monetary Fund, is to provide financial stability, which is, as we all understand it, the stepping stone for a successful economy. No stability, no growth.

Instead Mme. Lagarde and others talked of the importance of increasing jobs and pay for women, for income equality, for more old age pensions and social inclusion, climate change and indigenous rights.

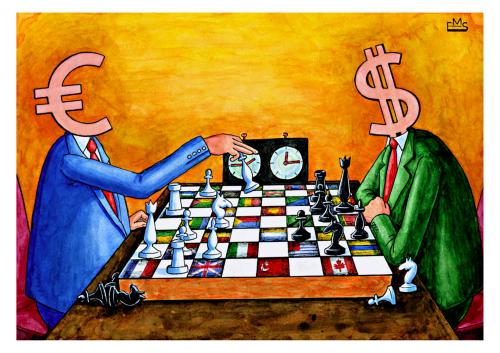

There was no talk, or hardly any, about exchange rates, nor even interest rates. Mme Lagarde and her crew are paid to control exchange rates. Dollars, euros, yen, renmunbi, pesos, reales, fluctuate today as dramatically as, and more unpredictably than, oil, gold and silver. Indeed, it is often the volatile currencies that push and pull the prices of commodities and most other things besides. Tails wagging the dogs. Carpet weavers in Kazakhstan and quinoa farmers on the Altiplano see their fortunes zoom or doom if the Fed in D.C. increases, or not, $ interest rates by a quarter point..

This is exactly how it should not be. The Fund was set up 70 years ago at the end of WWII to say Never Again to the disastrous competitive devaluations and desperate inflations and deflations that followed World War I. It was these crashing swings and roundabouts that set the scene for the Great Depression and World War II.

The IMF’s job was to keep European, and later the rest of the world, exchange rates fixed or at least stable.

The Fund never really knew, and as we see still does not know, what to do about exchange rates. Or rather, they always have had a theory but the theory keeps changing.

Fast forward to Lima 2015, with trillions of dollars and the others zooming beyond the control of the IMF, the Fed or anyone else. Peru has chosen this past couple of years not to devalue the Sol against the euro and the yen, and only slightly against the US dollar. Meanwhile neighbors like Brazil, Chile and Colombia have strongly devalued their pesos and reales.

Peru has over the past two years burned $24bn of its reserves to stabilize, as the Central Bank puts it, its currency and, one is to suppose, the economy. But the economy has slowed over the past 12 months to a whisker over 2%. Certainly the IMF and the other experts provided no ideas, much less clear guidance.

Until the United States, Europe and Japan put their houses in order, which is their constant advice to third world backsliders, there is not much the rest of us can do.