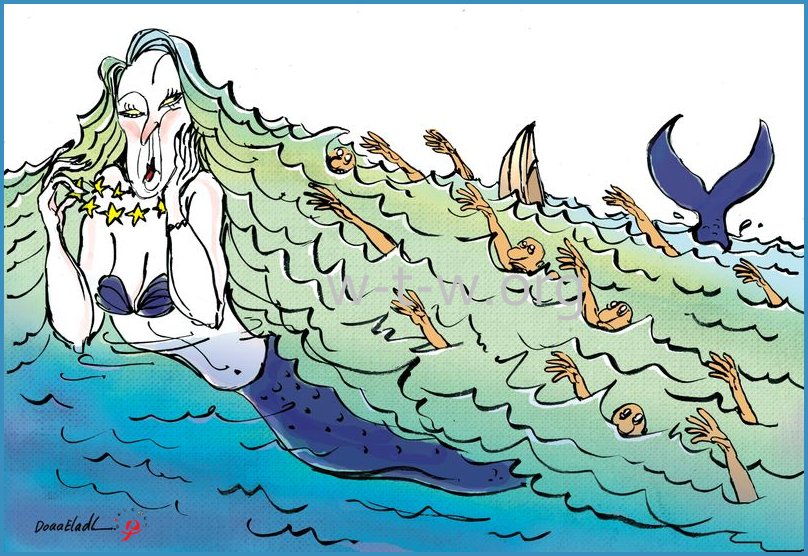

Nihda Sinha writes: As 2015 draws to a close, the outlook for global growth looks negative. On Wednesday, International Monetary Fund (IMF) managing director Christine Lagarde raised concerns over the issue.

Global economic growth will be disappointing next year and the outlook for the medium-term has also deteriorated. Lagarde said the prospect of rising interest rates in the US and an economic slowdown in China were contributing to uncertainty and a higher risk of economic vulnerability worldwide.

Although weak global growth remains a drag, Janet Yellen of the US Fed has said the US was far more dependent on domestic consumption and investment, which, at least so far, has been strong enough to produce growth that was slightly above trend.

Though the Reuters polls point to global growth averaging only 3.4% next year with scant prospect of touching 4%, given the slowdown in China and the gloom surrounding emerging markets, India seems to be on a better footing.

Last week, World Bank chief economist Kaushik Basu said amidst sluggish global growth, the US and India are two engines of growth with India anticipated to be among the fastest growing major economies in the world.

Addressing the 98th annual conference of the Indian Economic Association (IEA), Basu said, “Global growth is sluggish. The world economy is expected to grow barely by 2.5%.”

He noted that Russia is in recession and its GDP is actually shrinking by about 4%. Among the BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) nations, only China and India are growing around and below 7%, while Brazil’s GDP is declining by about 3.5% and South Africa is barely growing.

The Indian economy has the potential to be the world’s fastest growing economy over the coming decade, surging ahead of its South Asian economic rival China that will continue to see a slowdown, according to the Harvard University research.

A new economic reality of lower oil and commodity prices, lower growth in Asia and a normalizing US interest-rate environment represent an inflection point for the global economy. These developments will likely result in a volatile global environment.

“The global economy is recovering, but there are some wide regional disparities,” said Gabriel Torres, vice-president and senior credit officer at Moody’s. “Current and prospective growth rates are still generally lower than before the financial crisis.”

A sharp slowdown in China’s GDP growth rate to 2.3% during 2016-2018 “would disrupt global trade and hinder growth, with significant knock-on effects for emerging markets and global corporates. In turn, this would keep short-term interest rates and commodity prices lower for longer”, the report warned.

The UN cut its forecast for global economic growth in 2015 by 0.4 percentage point to 2.4%, largely due to lower commodity prices, increased market volatility and slow growth in emerging market economies, but added that there will be a slight pick-up next year.

“The world economy is projected to grow by 2.9% in 2016 and 3.2% in 2017, supported by generally less restrictive fiscal and still accommodative monetary policy stances worldwide,” the UN said in a statement accompanying its annual World Economic Situation and Prospects report.

In its latest 2015 Global Economic Prospects report, released in June 2015, the World Bank laid out the challenges. Developing countries face a series of tough challenges in 2015, including the looming prospect of higher borrowing costs in a new era of low prices for oil and other key commodities. This will result in a fourth consecutive year of disappointing economic growth this year, said the report. Developing countries are now projected to grow by 4.4% this year, with a likely rise to 5.2% in 2016, and 5.4% in 2017.