The overall mood was described by many as “gloomy” at the World Economic Forum. Others were “cautiously optimistic.” Discussions focused on whether China’s transition to a new growth model will continue to unsettle markets, whether the flow of refugees will fracture Europe’s unity, whether robots will replace people and jobs, and whether the global economy can start to fire on all cylinders to produce more sustainable and inclusive growth.

The road ahead is going to be bumpy, these transitions can be broadly helpful to the global economy — provided they are well managed and that countries implement smart policies.

The International Monetary Fund are supporting our 188 member nations in that effort. We do this through our core activities — lending, policy advice, and technical assistance — as well as by helping to deal with a set of emerging issues that are of increasing importance to them: female empowerment, energy and climate change, and reducing excessive inequality.

These issues are what we call “macro-critical” — essential to boost growth that is both durable and inclusive.

Christine Lagarde speaks out for equaity:

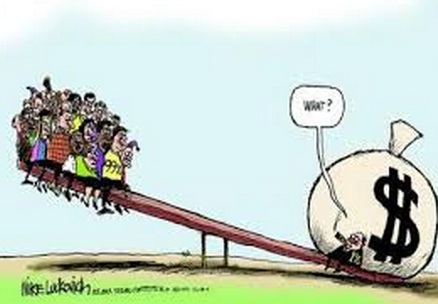

Take inequality, for example. The traditional argument has been that income inequality is a necessary by-product of growth, that redistributive policies to mitigate excessive inequality hinder growth, or that inequality will solve itself if you sustain growth at any cost.

Based upon world-wide research, the IMF has challenged these notions. In fact, we have found that countries that have managed to reduce excessive inequality have enjoyed both faster and more sustainable growth. In addition, our research shows that when redistributive policies have been well designed and implemented, there has been little adverse effect on growth.

Indeed, low growth and high inequality are two sides of the same coin: Economic policies need to pay attention to both prosperity and equity.

Increasing women’s economic participation in the labor market is another potentially game-changing contributor to greater and more equitable growth. In reviewing 143 countries, we found that almost 90 percent of them have at least one important legal restriction that makes it difficult for women to work.

Moreover, women face a double disadvantage in the job market: They are less likely to have a paid job than men and, if they get a job, they will earn significantly less than their male colleagues — even with the same level of education and in the same occupation.

Eliminating these employment gender gaps could boost GDP significantly — for instance, by 5 percent in the United States, 9 percent in Japan, and 27 percent in India. The potential to spur growth and reduce inequality also applies to the environment and energy policies. Like many others, I was encouraged when the world leaders signed the global climate agreement in Paris last December. But this is only the beginning. Signed agreements now need to be implemented.

Again, IMF research has indicated that carbon pricing could be transformative, both in freeing up additional resources for investments in health and education and in helping to preserve the planet.

These issues are key to a better global economy that benefits everyone. But there is no silver bullet. The drivers of inequality — of opportunity as well as outcome — vary across countries, and there is no one-policy-fits-all solution.

What is crystal clear, however, is that excessive inequality is a burning issue in most parts of the world, and that too many poor and middle-class households increasingly feel that the current odds are stacked against them. The overriding challenge facing policy makers in 2016 is to prove them wrong.

What Pope Francis has called “the globalization of indifference” must be addressed. More than anything else, that is what was on my mind when I left Davos last week.