More than halfway through his five-year term as president of China and general secretary of the Chinese Communist Party—expected to be the first of at least two—Xi Jinping’s widening crackdown on civil society and promotion of a cult of personality have disappointed many observers, both Chinese and foreign, who saw him as destined by family heritage and life experience to be a liberal reformer. Many thought Xi must have come to understand the dangers of Party dictatorship from the experiences of his family under Mao’s rule. His father, Xi Zhongxun (1913–2002), was almost executed in an inner-Party conflict in 1935, was purged in another struggle in 1962, was “dragged out” and tortured during the Cultural Revolution, and was eased into retirement after another Party confrontation in 1987.

Both father and son showed a commitment to reformist causes throughout their careers. Once Xi acceded to top office he was widely expected to pursue political liberalization and market reform. Instead he has reinstated many of the most dangerous features of Mao’s rule: personal dictatorship, enforced ideological conformity, and arbitrary persecution.

The key to this paradox is Xi’s seemingly incongruous veneration of Mao. With respect to Xi’s purge in 1962, the biography blames Mao’s secret police chief, Kang Sheng, rather than Mao himself, and claims that Mao protected Xi by sending him to a job in a provincial factory safely away from the political storms in Beijing. Xi’s respect for Mao is not a personal eccentricity. It is shared by many of the hereditary Communist aristocrats form most of China’s top leadership today as well as a large section of its business elite. Deng Xiaoping in 1981 declared that Mao’s contributions outweighed his errors by (in a Chinese cliché) “a ratio of 7 to 3.”

Their reverence for Mao is different from the simple nostalgia of former Red Guards and sent-down youth who hazily remember a period of adolescent idealism. The children of the founding elite see themselves as the inheritors of an “all-under-heaven,” a vast world that their fathers conquered under Mao’s leadership. Their parents came from poor rural villages and rose to rule an empire. The second generation is privileged to live in a country that has “stood up” and is globally respected and feared. They do not propose to be the generation that “loses the empire.”

It is this logic that drives Liu Yuan, the son of former president Liu Shaoqi, whom Mao purged and sent to a miserable death, to support Xi in reviving Maoist ideas and symbolism; and the same logic has moved the offspring of many of Mao’s other prominent victims to form groups that celebrate Mao’s legacy, like the Beijing Association of the Sons and Daughters of Yan’an and the Beijing Association to Promote the Culture of the Founders of the Nation.1

Xi holds office at a time when the regime has to confront a series of daunting challenges that have all reached critical stages at once. It must manage a slowing economy; mollify millions of laid-off workers; shift demand from export markets to domestic consumption; whip underperforming giant state-owned enterprises into shape; dispel a huge overhang of bad bank loans and nonperforming investments; ameliorate climate change and environmental devastation that are irritating the new middle class; and downsize and upgrade the military. Internationally, Chinese policymakers see themselves as forced to respond assertively to growing pressure from the United States, Japan, and various Southeast Asian regimes that are trying to resist China’s legitimate defense of its interests in such places as Taiwan, the Senkaku islands, and the South China Sea

Any leader who confronts so many big problems needs a lot of power, and Mao provides a model of how such power can be wielded. Xi Jinping leads the Party, state, and military hierarchies by virtue of his chairmanship of each. But his two immediate predecessors, Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao, exercised these roles within a system of collective leadership, in which each member of the Politburo Standing Committee took charge of a particular policy or institution and guided it without much interference from other senior officials.

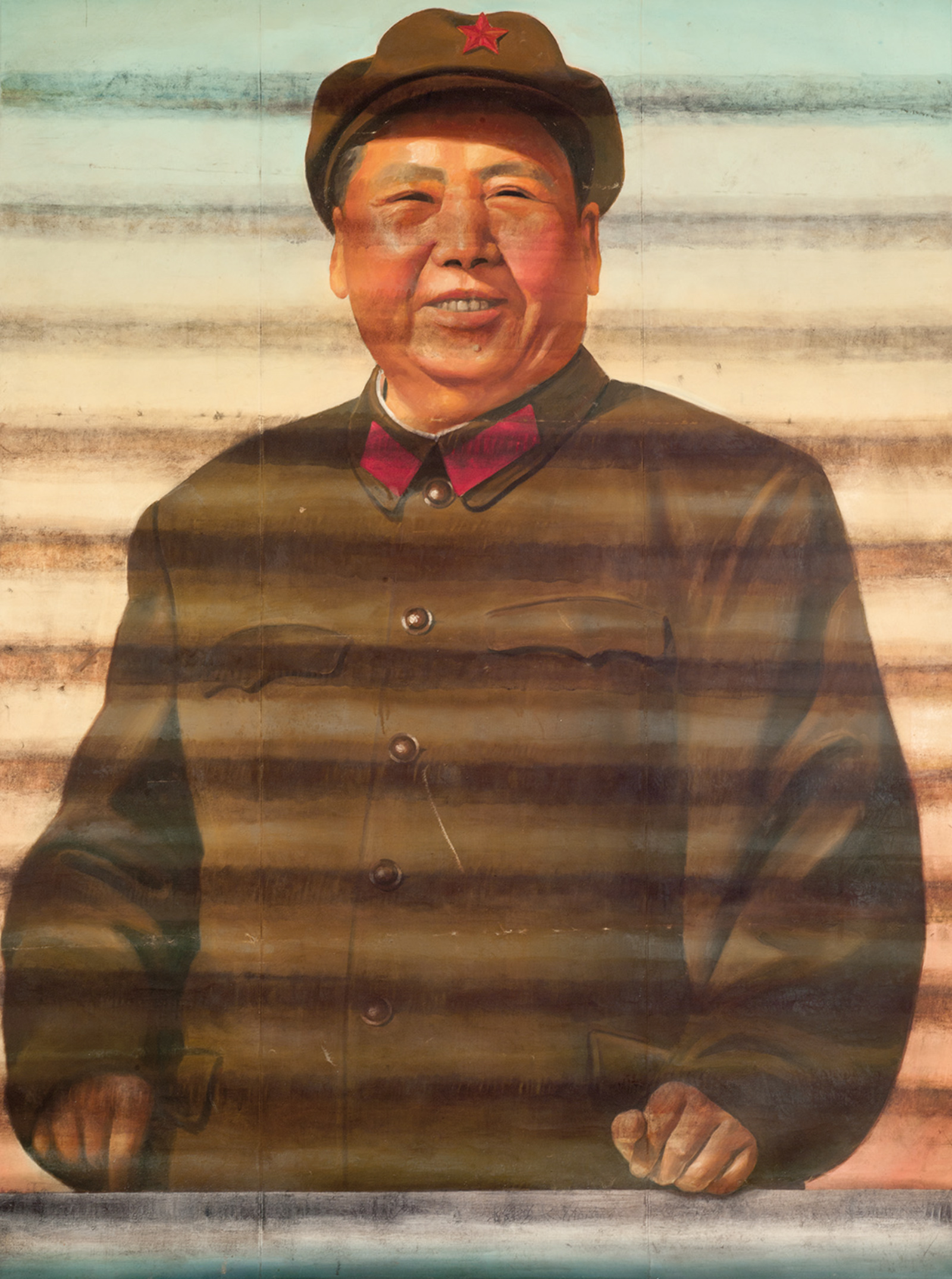

Ai Weiwei: Mao (Facing Forward), 1986; from the exhibition ‘Andy Warhol/Ai Weiwei,’ which originated at the National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, and will be at the Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh, June 4–August 28, 2016. The catalog is edited by Max Delany and Eric Shiner and published by Yale University Press.

Xi emulates Mao in exercising power through a tight circle of aides whom he can trust because they have demonstrated their personal loyalty in earlier phases of his career, such as Li Zhanshu, director of the all-powerful General Office of the CCP Central Committee.

Xi has also followed Mao’s model in protecting his rule against a coup. His anticorruption campaign has made him numerous enemies. Xi has tightened direct control over the military by means of what is called a “[Central Military Commission] Chairman Responsibility System,” and he controls the central guard corps—which monitors the security of all the other leaders—through his longtime chief bodyguard, Wang Shaojun.3 In these ways Xi controls the physical environment of the other leaders, just as Mao did through his loyal follower Wang Dongxing.

Xi conveys Napoleonic self-confidence in the importance of his mission and its inevitable success. In person he is said to be affable and relaxed. But his carefully curated public persona follows Mao in displaying a stolid presence and immobile features that seem to convey either stoicism or implacability.

Above all, Xi has followed Mao in the demand for ideological conformity. Xi wants “rule by law,” but this means using the courts more energetically to carry out political repression and change the bureaucracy’s style of work. He wants to reform the universities, not in order to create Western-style academic freedom but to bring academics and students to heel (including those studying abroad). He has launched a thorough reorganization of the military, which is intended partly to make it more effective in battle, but also to reaffirm its loyalty to the Party and to him personally. The overarching purpose of reform is to keep the Chinese Communist Party in power.

He may go even further. There are hints that he will seek to break the recently established norm of two five-year terms in office and serve one or even more extra terms.

Xi’s concentration of power poses great dangers for China.