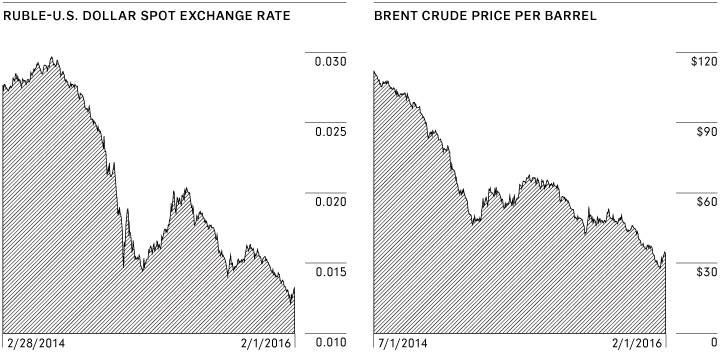

Can things get worse in Russia? Last year, as other money managers were steering clear of Russia’s broken economy, the Moscow-born Barinov pulled off something of a coup: He persuaded his bosses to take the plunge and buy Russian government bonds. It was a narrow bet, but he ended up winning because the central bank—after implementing the biggest interest rate hike since the Russian financial crisis in 1998 to prop up the collapsing ruble—changed course and aggressively backtracked. In the first 10 months of 2015, ruble-denominated government bonds handed investors such as Barinov a 25 percent return in dollar terms, the biggest gain for local bonds anywhere.

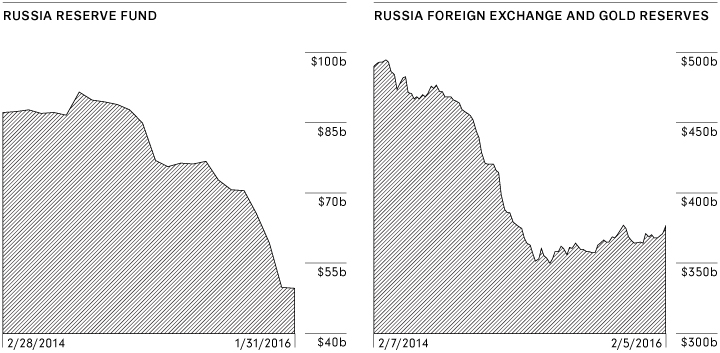

This year not even Barinov can spot an escape from the rubble of an economy mired in its longest recession in two decades, Bloomberg Markets magazine reports in its forthcoming issue. Sanctions imposed by the U.S. and the European Union to punish President Vladimir Putin for meddling in Ukraine remain a drag on growth. And oil’s decline to a 13-year low has been catastrophic for Russia, where almost 50 percent of government revenue comes from crude and natural gas. “With oil, you rely on a very volatile factor,” says Barinov, who oversees about $2.6 billion in assets. So as far as he’s concerned, “all bets are off.”

A persistent glut in crude supply could push prices to as low as $16 a barrel this year, according to former Russian Finance Minister Alexei Kudrin. Kudrin won plaudits overseas for his stewardship of Russia’s finances during Putin’s first decade in power. As the current crisis deepened, Bloomberg News reported in December, he was in discussions about a possible return to government. (He declined to comment on that.) A Putin ally, Kudrin remains negative about Russia’s prospects. “Over the next year to 18 months,” he says, “Russia will suffer major economic difficulties.”

In mid-January, as snow blanketed Moscow, the mood was grim at the Gaidar Forum, a kind of Russia-focused mini-Davos. The yearly economic conference is named after the free-market Russian economist Yegor Gaidar, who pioneered the shock therapy that introduced capitalism to Russia in the early 1990s. Finance Minister Anton Siluanov set the tone for the event, warning that without deep budget cuts to keep the deficit at 3 percent, the country risks a financial crash like that of the late ’90s, when Russia defaulted on its debts, the ruble crashed, and inflation spun out of control.