One currency implausible?

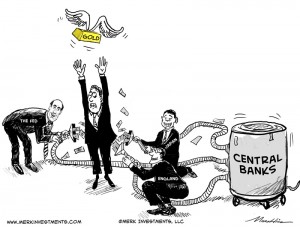

Larry Hatheway and Alexander Friedman write: Central banks, while ideally independent from political influence, are nonetheless accountable to the body politic. They owe their legitimacy to the political process that created them, rooted in the will of the citizenry they were established to serve (and from which they derive their authority).

The history of central banking, though comparatively brief, suggests that democratically derived legitimacy is possible only at the level of the nation-state. At the supra-national level, legitimacy remains highly questionable, as the experience of the eurozone amply demonstrates. Only if the European Union’s sovereignty eclipses, by democratic choice, that of the nation-states that comprise it will the European Central Bank have the legitimacy it requires to remain the eurozone’s sole monetary authority.

But the same political legitimacy cannot be imagined for any transatlantic or trans-Pacific monetary authority, much less a global one. Treaties between countries can harmonize rules governing commerce and other areas. But they cannot transfer sovereignty over an institution as powerful as a central bank or a symbol as compelling as paper money.

Central banks’ legitimacy matters most when the stakes are highest. Everyday monetary-policy decisions are, to put it mildly, unlikely to excite the passions of the masses. The same cannot be said of the less frequent need (one hopes) for the monetary authority to act as lender of last resort to commercial banks and even to the government. As we have witnessed in recent years, such interventions can be the difference between financial chaos and collapse and mere retrenchment and recession. And only central banks, with their ability to create freely their own liabilities, can play this role.

Yet the tough decisions that central banks must make in such circumstances – preventing destabilizing runs versus encouraging moral hazard – are simultaneously technocratic and political. Above all, the legitimacy of their decisions is rooted in law, which itself is the expression of democratic will. Bail out one bank and not another? Purchase sovereign debt but not state or commonwealth (for example, Puerto Rican) debt? Though deciding such questions at a supranational level is not theoretically impossible, it is utterly impractical in the modern era. Legitimacy, not technology, is the currency of central banks.

But the fact that a single global central bank and currency would fail spectacularly (regardless of how strong the economic case for it may be) does not absolve policymakers of their responsibility to address the challenges posed by a fragmented global monetary system. And that means bolstering global multilateral institutions.

The International Monetary Fund’s role as independent arbiter of sound macroeconomic policy and guardian against competitive currency devaluation ought to be strengthened. Finance ministers and central bankers in large economies should underscore, in a common protocol, their commitment to market-determined exchange rates. And, as Raghuram Rajan, the governor of the Reserve Bank of India, recently suggested, the IMF should backstop emerging economies that might face liquidity crises as a result of the normalization of US monetary policy.

Likewise, a more globalized world requires a commitment from all actors to improve infrastructure, in order to ensure the efficient flow of resources throughout the world economy. To this end, the World Bank’s capital base in its International Bank for Reconstruction and Development should be increased along the lines of the requested $253 billion, to help fund emerging economies’ investments in highways, airports, and much else.

Multilateral support for infrastructure investment is not the only way global trade can be revived under the current monetary arrangements. As was amply demonstrated in the last seven decades, reducing tariffs and non-tariff barriers would also help – above all in agriculture and services, as envisaged by the Doha Round.

Global financial stability, too, can be strengthened within the existing framework. All that is required is harmonized, transparent, and easy-to-understand regulation and supervision.

For today’s international monetary system, the perfect – an unattainable single central bank and currency – should not be made the enemy of the good. Working within our existing means, it is surely possible to improve our policy tools and boost global growth and prosperity.