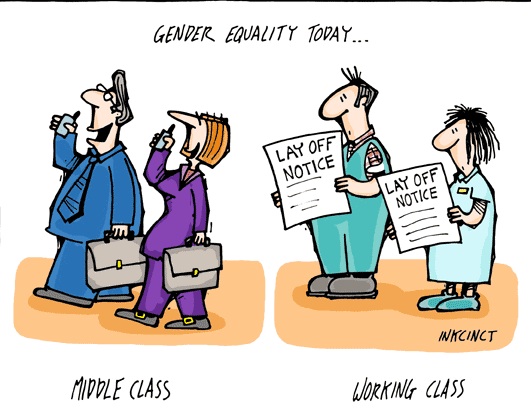

While speaking on the sidelines of a meeting in the Turkish capital Ankara in early September, Christine Lagarde, the International Monetary Fund chief, declared that India’s GDP would be 27 per cent higher if the country had as many of its women working as men.

India is not the only country failing to tap women’s productive potential for its overall economic growth and prosperity. Ms Lagarde also said Turkey’s per capita income would increase 22 per cent if it achieved gender parity in the workforce, and even Japan and the US could increase their GDP by 5 and 9 per cent respectively with workforce gender parity.

“The SDGs are very aspirational,” says Poonam Muttreja, executive director of the Population Foundation of India. “Only if we have high, high aspirations can we ever begin to have a sense of inequality being tackled.”

The SDGs predecessors, the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), committed the international community to “promote” gender equality and empower women, as well as separately to improve maternal health, to reduce the number of women dying in childbirth each year.

In some areas, progress was impressive. According to a UN report, the number of girls in school — the main measure of progress in “promoting” gender quality in the MDGs — has increased substantially over the past 15 years, as about two-thirds of the world’s developing countries achieved gender parity in primary school enrolment.

In south Asia’s primary schools, for example, 103 girls are now enrolled for every 100 boys, compared with just 74 girls for every 100 boys in 1990. This was partly a result of India’s huge school building boom, and midday meal schemes, which made schools more accessible to girls in rural areas and provided an incentive to attend.

In contrast preventing women from dying in childbirth — and sparing them from unwanted pregnancies — has been tougher. Worldwide, the maternal mortality rate has fallen 45 per cent since the 1990s, from 380 deaths per 100,000 live births to 210 deaths per 100,000. But it remains stubbornly high compared with middle-income countries such as Thailand, which has a maternal mortality rate of 26 per 100,000.

About 71 per cent of global births are attended by a skilled health worker, up from 59 per cent in 1990s. Use of contraceptives remains limited, with just 64 per cent of sexually active women of reproductive age using them, up from 55 per cent in 1990.

The SDGs are meant to build on progress made towards the MDGs, but they are also much more far-reaching in their ambitions. The third goal, for example, is “promoting healthy lives for all, and wellbeing for all at all ages”.

As part of that, it sets a target of reducing maternal mortality to below 70 per 100,000 live births by 2030, ensuring universal access to reproductive and sexual health services, and bringing gender parity to higher — as well as primary — education.

But in the quest to achieve gender equality, the SDGs call not just for the provision of stronger services, but for the changing of patriarchal attitudes and practices, such as child marriage and female genital mutilation.

Other targets call for ending all discrimination against women and girls and all violence against women. In India, that would presumably include ending the widespread practice of sex-selective abortions to prevent the birth of daughters. It also calls for propelling more women into leadership roles at all levels of decision-making in political, economic and public life.

Gender perspectives and special indicators for women have also been woven into many of the other SDG goals, including in such areas as education and access to employment. “The SDGs will force countries to look at gender-disaggregated data for all the issues,” says Ms Muttreja.

While the many targets pertaining to women’s lives outlined in the SDGs may seem too diffuse to lead to tangible results, Ms Muttreja believes the goals will be a big step towards tackling the constraints on women’s lives.