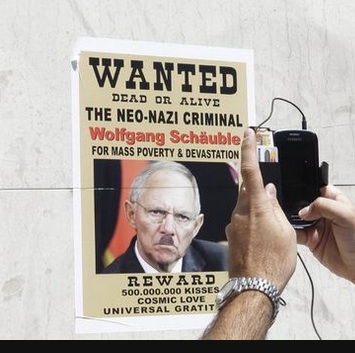

In Athens Wolfgang Schaeuble has been labelled a “bloodsucker” and a “Wanted” poster has appeared showing him with a Hitler mustache.

He may go down in history as the man with a Grexit plan.

He was behind a proposal to offer Greece a five-year “time-out” from the eurozone if no credible bailout could be agreed.

The final deal sets out a strategy to keep Greece in the euro – and the Grexit plan was not on the eurozone ministers’ agenda. Ms Merkel said Grexit would only be an option if Greece had asked for it, but Greece insisted on staying in the euro.

Under Mr Schaeuble’s plan, Grexit would make it possible to give Greece large-scale debt relief – something that would not be in line with current eurozone rules.

In the end, the overriding priority of keeping the eurozone intact trumped any talk of Grexit.

There were frayed nerves in the hours of tough talking. At one point, reports said, Mr Schaeuble snapped at European Central Bank chief Mario Draghi: “Do you take me for a fool?”

The bruising summit forced Mr Schaeuble to give some ground – there are now plans to extend Greece’s debt repayment schedules. And many believe that billions of euros owed by Greece will never be recovered.

According to Greece’s ex-Finance Minister Yanis Varoufakis, Mr Schaeuble wanted Greece to be “pushed out of the single currency to put the fear of God into the French and have them accept his model of a disciplinarian eurozone”.

When proposals emerged for €50bn of Greek assets to be placed in a Luxembourg fund, it was pointed out that the fund was a subsidiary of a bank in which Mr Schaeuble himself was a board member.

Mr Schaeuble became finance minister in 2009, in the midst of the global financial crisis, having served previously as German interior minister and CDU leader.

In his key role at the heart of the eurozone – with Germany the biggest contributor to EU bailouts – he has performed a double act with Ms Merkel, enforcing budget discipline.

They argue that relaxing the rules only encourages “moral hazard” – the reckless borrowing of the pre-crisis bubble years.

Yet back in 2003 France and Germany broke EU budget deficit rules. And critics say it is unfair for Germany to claim the moral high ground since it benefited from massive debt relief after World War Two.

Mr Schaeuble’s role as “Europe’s enforcer” is driven partly by the need to keep skeptical CDU and Bavarian CSU politicians on board. There is much German opposition to the eurozone bailout. Mr Schaeuble was formerly a rival of Ms Merkel. She replaced him as CDU leader in 2000 when his reputation took a battering in a CDU party funding scandal under ex-Chancellor Helmut Kohl.

He admitted that he had met the arms dealer and lobbyist at the centre of the scandal, Karlheinz Schreiber, and accepted an undeclared DM100,000 (£36,300) cash donation from him.

However, he denied doctoring CDU records or any other wrongdoing.