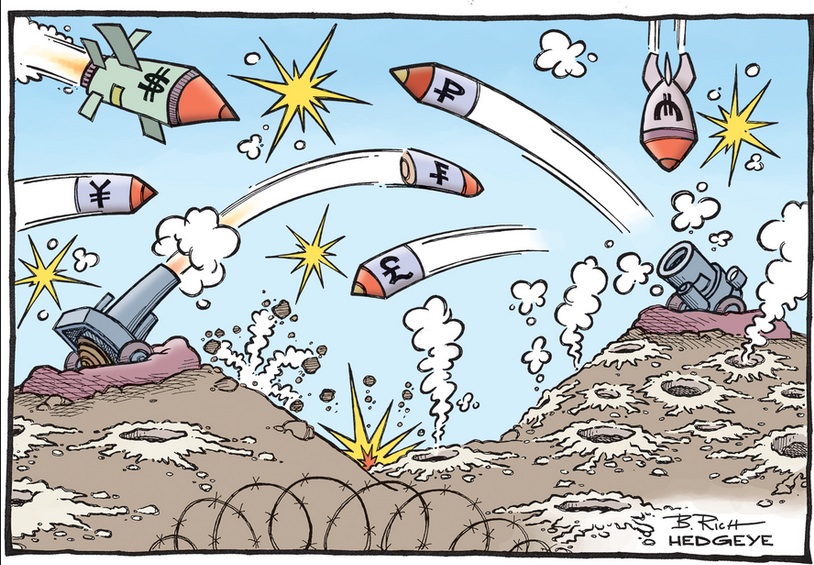

Kemal Davis writes: It is impossible to deny that trade and exchange rates are closely linked. But does that mean that international trade agreements should include provisions governing national policies that affect currency values?

Some economists certainly think so. Simon Johnson, for example, recently argued that mega-regional agreements like the Trans-Pacific Partnership should be used to discourage countries from intervening in the currency market to prevent exchange-rate appreciation;

As it stands, the relevant international institutions — the World Trade Organization and the International Monetary Fund — are not organized to respond effectively to possible currency manipulation on their own. Incorporating macroeconomic policies affecting exchange rates into trade negotiations would require either that the WTO acquire the technical capacity (and mandate) to analyze and adjudicate relevant national policies or that the IMF join the dispute-settlement mechanisms that accompany trade treaties.

The most direct method is purchases of foreign assets. But, in a world of large short-term capital flows, central-banks’ policy interest rates – or even just announcements about likely future rates — also have a major impact. Moreover, quantitative easing affects exchange rates and trade, even if central banks purchase only domestic assets, as demonstrated by recent movements in the exchange rates of the dollar, the euro, and the yen.

Consider the problem that would be posed by the eurozone. Most eurozone countries have lately been forced to tighten fiscal policy, thereby reducing or eliminating their current-account deficits. As a result, the total eurozone trade surplus is now massive. Because individual eurozone members have no monetary-policy tools at their disposal, the only way that Germany can reduce its surplus while remaining in the eurozone is to conduct expansionary fiscal policy. The economist Stefan Kawalec has explicitly referred to the current policy mix in the eurozone as “currency manipulation.”

None of this means that macroeconomic policies that affect exchange rates are not problematic. They are. But trade negotiations are not the right forum for discussing the causes and consequences of current-account imbalances.

A better approach would include strengthening the IMF’s multilateral surveillance role. Doing so would broaden discussions of macroeconomic policy to include employment issues — specifically, the potential impact of large foreign-trade surpluses on domestic jobs. And it would give trade negotiations a chance to succeed.