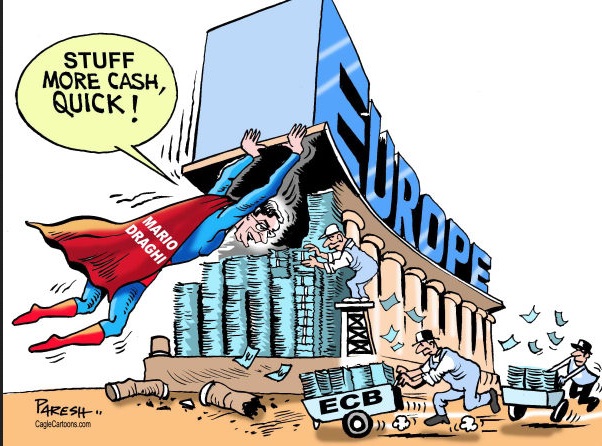

Mohamed El-Erian writes: European Central Bank President Mario Draghi painted a dovish and hopeful picture and was also realistic about what euro zone governments need to do to enable the ECB’s full success.

Draghi left no doubt the ECB is committed to the implementation of its “non-standard” monetary policy. He reiterated that the central bank “intends” to intervene in markets until the end of September 2016, regardless of concerns about negative nominal yields and a possible shortage in securities to purchase. And it would continue beyond that date if the bank doesn’t obtain the macroeconomic outcome the quantitative easing program is designed to achieve.

To make this point even more forcefully, Draghi dismissed concerns about QE’s inadvertent collateral damage. These include accentuating the future risks of financial instability and enabling governments to be less responsible.

Turning to the impact of QE, Draghi was optimistic about the initial results. He pointed to the improvement in credit flows and other monetary indicators; and he took comfort from the stronger momentum of the euro zone economy, notwithstanding substantial variations among countries. In doing so, he played down concerns that ECB policy was encouraging financial bubbles, though he only seemed focused on bank leverage.

What Draghi didn’t make clear is that the euro zone’s experience of QE closely resembles those of other countries that had previously undertaken such efforts, particularly Japan and the U.S.

As was the case elsewhere, the first stages of the ECB’s program were immediately met with a helpful response in financial markets, including higher equity prices, lower bond yields and a depreciated currency. This response boosted sentiment more broadly and partially spilled over into economic activity. That was the easy part, which I previously described as the first third of the QE journey.

The remaining two-thirds will be much harder. Success requires sustaining economic progress while, simultaneously, containing the “costs and risks” associated with artificially boosted asset prices and possible resource misallocations. To navigate that artfully, the ECB will need a lot of help from other institutions.

As noted by Draghi, the ultimate success of the ECB’s unconventional policy approach will require governments to implement deeper structural reforms — including in labor and product markets — as well as encourage business investment and expansion. It will need much more pronounced balance-sheet healing, including overcoming increasingly entrenched debt overhangs. And, in my opinion, it also needs aggregate demand within Europe to be higher and more evenly spread across countries.

Europe is still quite a distance from achieving any of this. The celebration of the encouraging start of the euro zone’s QE should be tempered by the lessons of similar policies elsewhere.