John Morgan and Bin Wu write: The number of university students in China, including those in part-time higher adult education, expanded from 12.3m students in 2000 to 34.6m in 2013. China has become an exceptional example of increasing access for students to higher education – but this expansion has also been accompanied by some unexpected and even negative consequences.

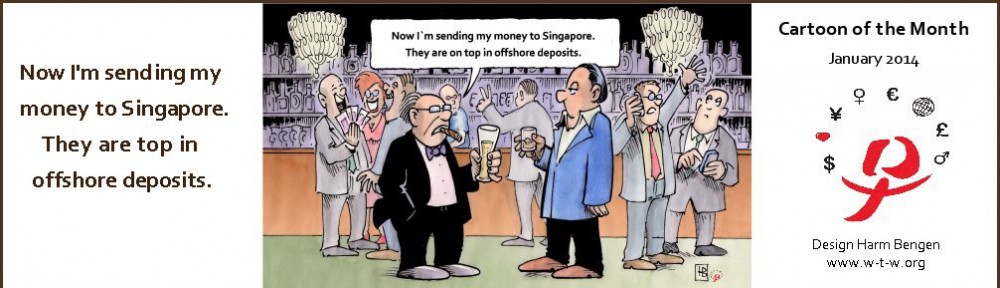

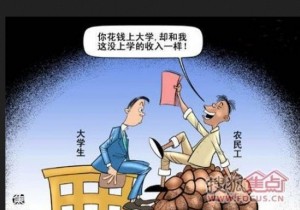

The annual number of graduates is expected to reach 7.27m in 2014. The challenge is to find them appropriate jobs, especially as the supply of over-educated graduates exceeds labour market demand.

The unevenness of China’s economic and social development over the past three decades has created a stratified scoiety which has had a major impact on educational inequality.

The renewal of higher education was a key part of Deng Xiaoping’s development strategy, begun in 1978, to open China to the world. State control was maintained and the universities continued to serve the policy requirements of the Communist Party.

Yet gradual adjustments were made. A high value was placed on scientific knowledge, innovation and the application of research, compared with traditional Chinese knowledge. University curricular were de-politicised and direct political control over student recruitment and behaviour was relaxed.

In contrast with the Maoist era, the most significant change has been that universities are now essentially centres for the production of elites in the manner of similar institutions in capitalist economies. The possession of university credentials is now emphasised as a key criterion for recruitment or promotion in both the public sector and in the emerging private sector.

In the late 1990s, China’s higher education system entered a new era, with the introduction of a new set of policies focused on developing world-class universities.

These led to strict ranking of higher education institutions with privileged state financial support. This was followed by the devolution of responsibility for around 300 other universities to provincial governments.

The most significant change has been a funding system which has led to both an expansion of public universities and the emergence of private higher education.

These changes have taken place in the context of an economic growth which has created a highly stratified society. Now policy programmes have aimed to increase the number of disadvantaged students accessing key universities, while state funds have been allocated to improve teaching conditions in higher education in the disadvantaged west of China.

Students from migrant workers’ families have been allowed to take the national university entrance examination at their place of residence rather than at their place of family origin. There has also been improved state financial support for students from poor families alongside promotion of entrepreneurship to enhance employment prospects.

The dilemma faced by Chinese higher education officials is how to build both world-class universities and a system that meets the needs of the Chinese people.