Daniel Gros writes: The mantra in Brussels and throughout Europe nowadays is that investment holds the key to economic recovery. The lynchpin of the new European Commission’s economic strategy is its recently unveiled plan to increase investment by €315 billion ($390 billion) over the next three years.

The Commission’s plan, the signature initiative of President Jean-Claude Juncker at the start of his term, comes as no surprise. With the eurozone stuck in a seemingly never-ending recession, the idea that growth-enhancing investment is crucial for a sustainable recovery has become deeply entrenched in public discourse.

European Union authorities (and many others) argue that Europe – particularly the eurozone – suffers from an “investment gap.” The smoking gun is supposedly the €400 billion annual shortfall relative to 2007.

But the comparison is misleading, because 2007 was the peak of a credit bubble that led to a lot of wasteful investment. The Commission recognizes this in its supporting documentation for the Juncker package, in which it argues that the pre-credit-boom years should be used as the benchmark for desirable investment levels today. According to that measure, the investment gap is only half as large.

The pre-boom years are not a good guide for today’s European economy, because something fundamental has changed more quickly than is typically recognized: Europe’s demographic trends.

The eurozone’s working-age population had been growing until 2005, but it will fall from 2015 onward. Given that productivity has not been picking up, fewer workers mean significantly lower potential growth rates. And a lower growth rate implies that less investment is needed to maintain the capital/output ratio.

If the eurozone maintained its investment rate at the level of the pre-boom years, there would soon be much more capital relative to the size of the economy.

An ever-increasing capital stock relative to output means ever-lower returns to capital and thus ever more non-performing loans in the banking sector over time.

What can the Juncker plan do to have a positive short-run impact on aggregate investment?

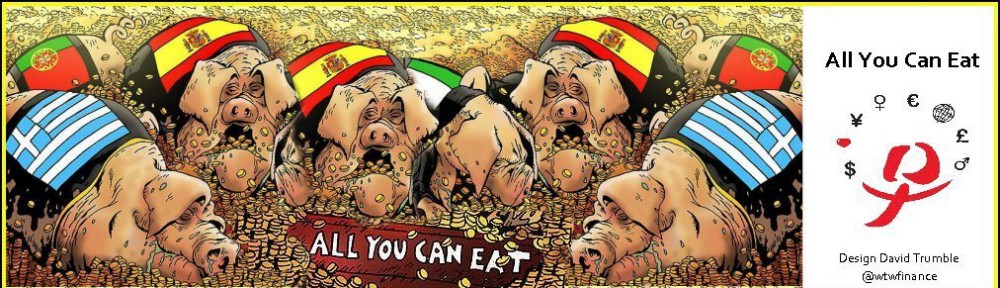

At present, there is no shortage of funding available in most of the EU. The countries on the eurozone periphery, where credit might still be scarce, account for less than one-quarter of Europe’s economy. So a lack of funding is not the reason that investment remains weak.

The Juncker plan is supposed to unlock, with €21 billion in EU funding, projects worth 15 times as much (€315 billion). That sounds far-fetched. Europe’s banking system already has more than €1 trillion in capital. The addition of €21 billion, in the form of guarantees from the EU budget, is unlikely to have a significant impact on banks’ willingness to finance investment.

The Juncker plan targets, in particular, infrastructure projects, which are often riskier than other investments. But these risks usually are not financial; they reflect potential political and regulatory barriers at the national level. These problems cannot be solved by a guarantee from the EU budget.

The reason why there still is no good interconnection between the Spanish and French power grids is not a lack of financing, but the unwillingness of monopolies on both sides of the border to open their markets. Many rail and road projects are also proceeding slowly, owing to local opposition, not a lack of financing.

.

Economic performance in the United States and the United Kingdom holds an important lesson for the eurozone. Both economies’ recoveries have been driven largely by a pickup in consumption on the back of stronger household balance sheets, especially in the US. Is consumption the answer?