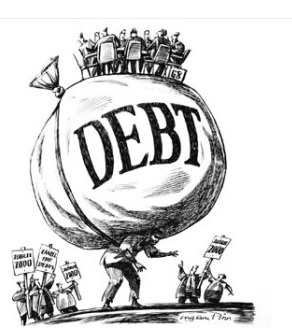

Carmen Reinhart writes: When it comes to sovereign debt, the term “default” is often misunderstood. It almost never entails the complete and permanent repudiation of the entire stock of debt. indeed, even some Czarist-era Russian bonds were eventually (if only partly) repaid after the 1917 revolution.

Like so many other features of the global economy, debt accumulation and default tends to occur in cycles.

The most recent default cycle includes the emerging-market debt crises of the 1980s and 1990s. Most countries resolved their external-debt problems by the mid-1990s, but a substantial share of countries in the lowest-income group remain in chronic arrears with their official creditors.

Such arrears are often swept under the rug, possibly because they tend to involve low-income debtors and relatively small dollar amounts.

Global economic conditions – such as commodity-price fluctuations and changes in interest rates by major economic powers such as the United States or China – play a major role in precipitating sovereign-debt crises. Peaks and troughs in the international capital-flow cycle are especially dangerous.

For some sovereigns, the main problem stems from internal debt dynamics.

Greece’s situation is all too familiar. Greece defaulted on its obligations to the IMF. That makes Greece the first – and, so far, the only – advanced economy ever to do so.

But, as is so often the case, what happened was not a complete default so much as a step toward a new deal. Greece’s European partners eventually agreed to provide additional financial support, in exchange for a pledge from Greek Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras’s government to implement difficult structural reforms and deep budget cuts. Unfortunately, it seems that these measures did not so much resolve the Greek debt crisis as delay it.

Another economy in serious danger is the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, which urgently needs a comprehensive restructuring of its $73 billion in sovereign debt. Recent agreements to restructure some debt are just the beginning; in fact, they are not even adequate to rule out an outright default.

Some of the biggest risks lie in the emerging economies, which are suffering primarily from a sea change in the global economic environment. During China’s infrastructure boom, it was importing huge volumes of commodities, pushing up their prices and, in turn, growth in the world’s commodity exporters, including large emerging economies like Brazil. Add to that increased lending from China and huge capital inflows propelled by low US interest rates, and the emerging economies were thriving. The global economic crisis of 2008-2009 disrupted, but did not derail, this rapid growth, and emerging economies enjoyed an unusually crisis-free decade until early 2013.

But the US Federal Reserve’s move to increase interest rates, together with slowing growth (and, in turn, investment) in China and collapsing oil and commodity prices, has brought the capital inflow bonanza to a halt.

From a historical perspective, the emerging economies seem to be headed toward a major crisis. Of course, they may prove more resilient than their predecessors. But we shouldn’t count on it.