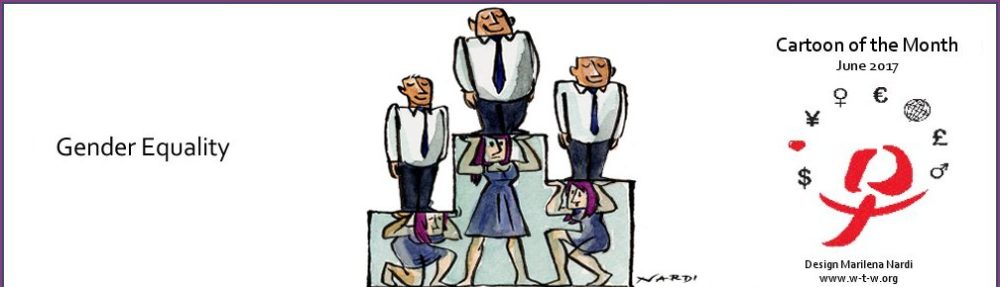

The systemic financial risk-taking in the lead up to the financial crisis was a product of untouchable insiders taking risks that favored the connected few. And the many still suffer. Cameron K. Murray write: Not only are there insider groups bridging Wall Street and financial regulators, but Defense Departments are a hotbed of revolving personnel into, and out of, private weapons and hardware manufacturers. At local government levels this type of revolving door of well-connected insiders is even more insidious, with land rezoning and infrastructure spending a constant battle between in the interests of the insiders and the community at large. The revolving door culture is now so pervasive that Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke, arguably the most powerful financial regulator in recent history, waltzed through the door to consult for a multi-billion dollar hedge fund with almost no media criticism. Few issues are more important than being governed in the interest of the few at the expense of the many. The economic costs of this behaviour are likely to be in the hundreds of billions of dollars annually. Yet from a standard economic viewpoint, the mechanism by which such favouritism occurs remains a mystery. To shine some light on the mechanisms in coordinating back-scratching, its costs, and potential institutional changes to combat it, I took the problem to the lab under computerised experimental conditions. While the results confirm a lot of common sense intuition, they are a leap forward in terms of our economic understanding of the problem. Regulatory capture is the name economists give to the perverse effects of the revolving door, yet its effects on behavior are not the product of a coherent theoretical framework. For regulators to act in the interests of their former, or potentially future, employers requires a level of implicit collusion that shouldn’t exist in a world of purely self-interested agents who would defect from any attempt to form a group of allied insiders. Something else must be going on. Another view in standard economics is that political favors are imagined to be auctioned by way of a lottery, where bidders devote their resources to non-productive activities, such as attending political fundraisers, up to the amount of their expected payoff from the political favor subject to the participation of others in the lottery. This is called rent-seeking. The prize of a political favour is open to anyone, and we should expect, just like we see in real lotteries, no specific entrenchment of particular interest groups and a high degree of randomness in allocation of political favors. Back-scratching, corruption and regulation

W-T-W.org

Women and Finance