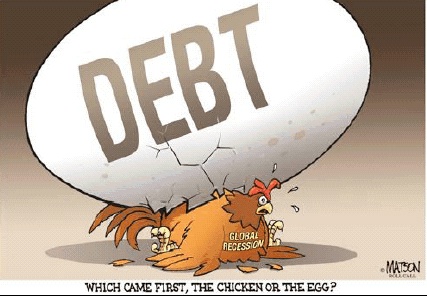

Richard Kozul Wright writes: Over the last few months, a great deal of attention has been devoted to financial-market volatility. But as frightening as the ups and downs of stock prices can be, they are mere froth on the waves compared to the real threat to the global economy: the enormous tsunami of debt bearing down on households, businesses, banks, and governments. If the US Federal Reserve follows through on raising interest rates at the end of this year, as has been suggested, the global economy – and especially emerging markets – could be in serious trouble.

Global debt has grown some $57 trillion since the collapse of Lehman Brothers in 2008, reaching a back-breaking $199 trillion in 2014, more than 2.5 times global GDP. Servicing these debts will most likely become increasingly difficult over the coming years, especially if growth continues to stagnate, interest rates begin to rise, export opportunities remain subdued, and the collapse in commodity prices persists.

Much of the concern about debt has been focused on the potential for defaults in the eurozone. But heavily indebted companies in emerging markets may be an even greater danger. Corporate debt in the developing world is estimated to have reached more than $18 trillion dollars, with as much as $2 trillion of it in foreign currencies. The risk is that – as in Latin America in the 1980s and Asia in the 1990s – private-sector defaults will infect public-sector balance sheets.

That possibility is, if anything, greater today than it has been in the past. Increasingly open financial markets allow foreign banks and asset managers to dump debts rapidly, often for reasons that have little to do with economic fundamentals. When accompanied by currency depreciation, the results can be brutal – as Ukraine is learning the hard way.

It is important to note that indebted governments are both more and less vulnerable than private debtors. Sovereign borrowers cannot seek the protection of bankruptcy laws to delay and restructure payments; at the same time, their creditors cannot seize non-commercial public assets in compensation for unpaid debts. When a government is unable to pay, the only solution is direct negotiations. But the existing system of debt restructuring is inefficient, fragmented, and unfair.

Sovereign borrowers’ inability to service their debt tends to be addressed too late and ineffectively. Governments are reluctant to acknowledge solvency problems for fear of triggering capital outflows, financial panics, and economic crises. Meanwhile, private creditors, anxious to avoid a haircut, will often postpone resolution in the hope that the situation will turn around. When the problem is finally acknowledged, it is usually already an emergency, and rescue efforts all too often focus on propping up irresponsible lenders rather than on facilitating economic recovery.

To make matters worse, when a compromise is reached, the burden falls disproportionately on the debtor, in the form of enforced austerity and structural reforms that make the residual debt even less sustainable.

As consensus grows regarding the need for better ways to restructure debt, three options have emerged. The first would strengthen bond markets’ legal underpinnings, by introducing strong collective-action clauses in contracts and clarifying the pari passu (equal treatment) provision, as well as promoting the use of GDP-indexed or contingent-convertible bonds.

A second approach would focus on building a consensus around soft-law principles to guide restructuring efforts. The core principles include sovereignty, legitimacy, impartiality, transparency, good faith, and sustainability principles – currently would apply to all debt instruments.

The third option would attempt to resolve this coordination problem through a set of rules and norms agreed in advance as part of an international debt-workout mechanism that would be similar to bankruptcy laws at the national level.

The mechanism would include provisions allowing for a temporary standstill on all payments due, whether private or public; an automatic stay on creditor litigation; temporary exchange-rate and capital controls; the provision of debtor-in-possession and interim financing for vital current-account transactions; and, eventually, debt restructuring and relief.

Evidence from Ghana, Greece, Puerto Rico, Ukraine, and many other countries shows the economic and social damage that unsustainable debts can cause when they are improperly managed.