John Kay writes: More than a half-century ago, John Kenneth Galbraith presented a definitive depiction of the Wall Street Crash of 1929. Embezzlement, Galbraith observed, has the property that “weeks, months, or years elapse between the commission of the crime and its discovery. This is the period, incidentally, when the embezzler has his gain and the man who has been embezzled feels no loss. There is a net increase in psychic wealth.” Galbraith described that increase in wealth as “the bezzle.”

Warren Buffett’s business partner, Charlie Munger, pointed out that the concept can be extended much more widely. This psychic wealth can be created without illegality: mistake or self-delusion is enough. Munger coined the term “febezzle,” or “functionally equivalent bezzle,” to describe the wealth that exists in the interval between the creation and the destruction of the illusion.

From this perspective, the critic who exposes a fake Rembrandt does the world no favor: The owner of the picture suffers a loss, as perhaps do potential viewers, and the owners of genuine Rembrandts gain little. The finance sector did not look kindly on those who pointed out that the New Economy bubble of the late 1990s, or the credit expansion that preceded the 2008 global financial crisis, had created a large febezzle.

It is easier for both regulators and market participants to follow the crowd. Only a brave person would stand in the way of those expecting to become rich by trading Internet stocks with one another, or would deny people the opportunity to own their own homes because they could not afford them.

The joy of the bezzle is that two people – each ignorant of the other’s existence and role – can enjoy the same wealth. Shareholders in banks could not have understood that the dividends they received before 2007 were actually money that they had borrowed from themselves.

Investors congratulated themselves on the profits they had earned from their vertiginously priced Internet stocks. They did not realize that the money they had made would melt away like snow in a warm spring.

Fair value accounting has multiplied opportunities for imaginary earnings, such as Enron’s profits on gas trading. If you measure profit by marking to market, then profit is what the market thinks it will be. The information contained in the accounts of the business – the information that should shape the market’s views – is to be derived from the market itself.

And the market is prone to temporary fits of shared enthusiasm. There are numerous routes to bezzle and febezzle. In a Ponzi scheme, early investors are handsomely rewarded at the expense of latecomers until the supply of participants is exhausted. Such practices, illegal as practiced by Bernard Madoff, are functionally equivalent to what happens during an asset-price bubble.

The essential story of the period from 2003 through 2007 is that banks announced large profits and paid a substantial share of them to their traders and senior employees. Then they discovered that it had all been a mistake, more or less wiped out their shareholders, and used taxpayer money to trade their way through to new levels of reported profit.

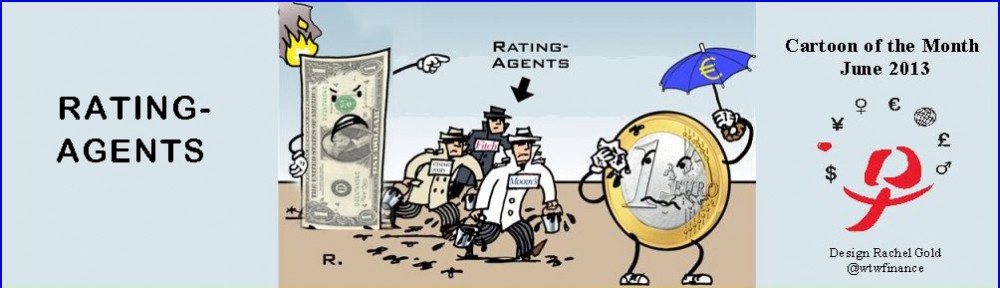

The essential story of the eurozone crisis is that banks in France and Germany reported profits on money they had lent to southern Europe and passed the bad loans to the European Central Bank. In both narratives, traders borrowed money from the future. And then the future came, as it always does, turning the bezzle into a bummer.