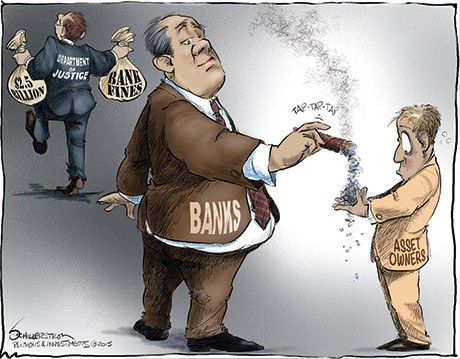

Hillary Clinton, the leading Democratic contender as the party’s nominee for President, came out with two proposals to make big banks safer. One is the tax high speed trading. The other, to hold bank executives accountable for crimes committed by underlings on their watch.

Paula Dwyer writes: Hillary Clinton has a wide-ranging plan to make Wall Street safer. It would make bankers defer some of their compensation so that it could be recovered later if their activities lead to losses that blow up the bank.

Increasing the statute of limitations on financial crimes to 10 years from six is legitimately hard-nosed, as are her proposals to hold bank executives accountable when subordinates break the law, and to beef up the budgets of agencies that police the markets.

The dozens of recommendations, though, seem designed to avoid having to reinstate the Glass-Steagall Act, the Depression-era law that separated commercial from investment banking. To call for Glass-Steagall’s comeback would create a big stink.

In this she risks achieving little and, in some cases, causing harm. This is especially true for her two biggest and most interesting ideas — a so-called risk fee on the largest banks and a tax on high-speed traders.

Her aim is to make these too-big-to-fail banks think twice about using leverage, peddling derivatives, packaging subprime mortgages into bonds, and the like. The problem is that this annual fee would come out of a bank’s capital (money raised from the sale of stock and retained profits). Regulators, however, should want banks to have as much capital as possible to absorb losses, in the way that a homeowner with 20 percent equity in a house wouldn’t be under water even if the home’s market value suddenly declined by 10 percent.

If Clinton really wanted to make the financial system safer, she would require banks to have more capital, making failure less likely in the first place. Instead, a bank could interpret payment of its risk fee as a license to behave in an even riskier manner.

Companies are trying to shave thousandths of a second off trading times, in part by putting their computer servers next to stock-market servers to reduce data-transmission times. High-speed traders use complex algorithms to place billions of buy and sell orders to sniff out demand and profit on split-second changes in price.

Meanwhile, traders cancel many more orders than they complete. Some traders have no intention of actually buying or selling the shares behind their orders, but are just probing the market. There are no real penalties for this strategy, although the Securities and Exchange Commission occasionally goes after trading strategies it finds especially abusive.

High-speed trading has also left the impression that markets aren’t fair or safe for ordinary investors.

Clinton obviously agrees, yet her solution is too blunt an instrument. Her tax would apply only to those with “excessive levels” of canceled orders. She doesn’t define excessive, possibly because it’s an impossible line to draw.

Many of Clinton’s fellow Democrats would prefer that she keep it simple and bring back Glass-Steagall. Her many supporters on Wall Street hate that idea, so her alternative proposals allow her to protect that part of her donor base while defending her husband’s legacy — all while signaling to voters that she’s no pushover. That might work politically — at the cost of getting anything done.