Jean Pisani Ferry writes: Most people hate finance, viewing it as the epitome of irresponsibility and greed. But, even after causing a once-in-a-century recession and unemployment for millions, finance looks indispensable for preventing an even worse catastrophe: climate change.

Action is urgently needed to contain global warming and prevent a disaster for humanity; yet the global community is desperately short of tools. There is not much support for the most desirable solutions advocated by economists, such as a global cap on greenhouse-gas emissions, coupled with a trading system, or the enforcement of a worldwide carbon price through a global tax on CO2 emissions.

Instead, negotiations for the United Nations Climate Change Conference in Paris in December are being conducted on the basis of voluntary, unilateral pledges called Intended Nationally Determined Contributions. Although the inclusion of voluntary targets has the merit of creating global momentum, this approach is unlikely to result in commitments that are both binding and commensurate to the challenge.

That is why climate advocates are increasingly looking for other means of triggering action. Finance is at the top of their list.

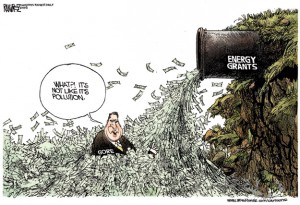

For starters, finance provides an accurate yardstick to gauge if deeds are consistent with words. In 2011, “Unburnable Carbon,” a path-breaking report by the nongovernmental Carbon Tracker Initiative, showed that the proven fossil-fuel reserves owned by governments and private companies exceed by a factor of five the quantity of carbon that can be burned in the next 50 years if global warming is to be kept below two degrees Celsius.

Reserves held just by the 200 top publicly listed fuel companies – thus excluding state-owned producers such as Saudi Arabia’s Aramco – exceed this carbon budget by one-third. And that means that these companies’ stock-market valuation is inconsistent with containing global warning.

This realization prompted a campaign to convince investors to divest from carbon-rich assets. Individuals and institutions representing a $2.6 trillion portfolio have already joined the divestment movement. Furthermore, Bank of England Governor Mark Carney has highlighted the threat represented by potentially stranded carbon assets. Investors are being warned that, from the standpoint of financial stability, “brown” securities bear specific risk.

The amount of divestment may look big – and it is, particularly given that the campaign started recently. Yet $2.6 trillion amounts to less than 5% of global private non-financial securities. The trend is real, but it is still too little to trigger significant changes in fossil-fuel companies’ valuation and behavior.

A second reason why finance matters is that the transition to a low-carbon economy requires huge investments. According to the International Energy Agency, global investment in energy supply currently amounts to $1.6 trillion annually, and 70% of it is still based on oil, coal, or gas. Green investment amounts to only 15% of the total, and investment in energy efficiency – in buildings, transport, and industry – totals a meager $130 billion. Containing the increase in average surface temperature to two degrees requires developing clean technologies, and even more important, a four-fold increase in investment in energy efficiency over the next ten years.

The real hope among climate specialists is that innovative finance could help provide the planning clarity that is currently missing. To elicit the investments that are necessary to mitigate climate change and green the economy, the elimination of fossil-fuel subsidies and a credible, fast-rising path for the price of carbon are vital. But, because high fuel prices are unpopular with consumers and raise competitiveness concerns among businesses, governments are reluctant to take action today – and may renege on their commitments to act tomorrow.

To overcome such trepidation, advocates for climate action are turning to incentives. Some have recommended that governments issue CO2 performance bonds, whose yield would be reduced if companies exceed their carbon target. Another idea, put forward in a recent paper by Michel Aglietta and his colleagues, is to map out a path for an indicative price of carbon called its “social value” and provide green project developers a government-guaranteed carbon certificate representing the value of the corresponding emissions reduction. Central banks, they suggest, would then refinance loans to such developers, up to the value of the carbon certificate.

This would amount to a calculated bet. If the price of carbon in, say, ten years, actually corresponds to the announced social value, the project will be profitable and the developer will repay the loan. But if the government reneges on its commitment, the developer will default, leaving the central bank with a claim on the government. Failure to increase the price of carbon would result either in higher public debt or, in the case of monetization, inflation.

The idea is to force governments to have skin in the game, by balancing the risk of inaction on the carbon tax with the risk of insolvency or inflation. There would be no procrastination. Action against global warming would take place without delay. But a decade or so later, governments – and societies more broadly – would need to choose between taxation, debt, and inflation.

Undertaking massive investment now and deciding only later how to finance it looks irresponsible – and so it is. But not acting at all would be even more irresponsible.