Ronald Tiersky writes: Remembering history is crucial to understanding the present. Its lessons can be ignored or badly played, but a knowledge of history helps steer us away from exaggerated, immediate conclusions anchored in the flow of the quotidian.

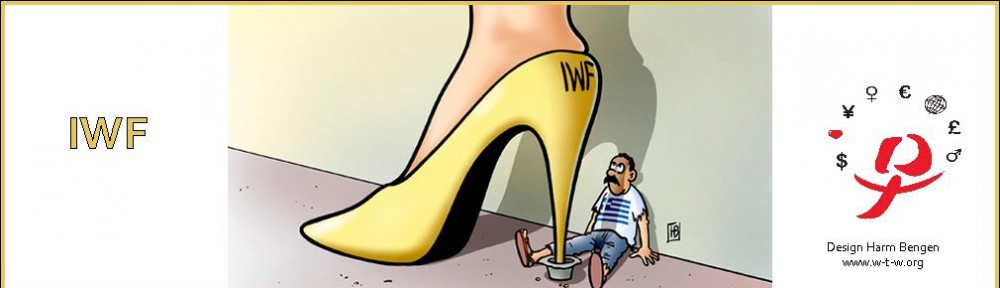

European integration provides a stellar example. The history of this process frames the deal just reached between Greece and its creditors. It helps us to understand.

The European Union’s pattern has always been to make significant advances by crisis. After the trouble ebbs, a period of stability follows as the new order is established, until stagnation or some outside event leads to a new crisis, with a new solution that works more or works less but sets up the cycle anew.

Europe should take some comfort in the fact that in politics, nothing is absolutely certain, and nothing is forever. The euro currency, the European monetary system — indeed, even European integration itself — could always end in catastrophe. Yet if history is good enough of a guide, this is anything but a foregone conclusion.

Another truism: In politics nothing is ever permanently won or lost. European integration has been written off many times before yet it has survived — perhaps with different structures than intended, and with solutions that are less than perfect, but it has come a long way. (And as Charles de Gaulle wrote, “the future lasts a long time.”)

The most historically informed criticism of EU Economic and Monetary Union, which was set up in the Maastricht Treaty of 1992, argues that the arrangement lacked the necessary precondition to be run effectively: that is, political union. Choices in macroeconomic policies are fundamentally political decisions. Absent the political concessions on national sovereignty necessary for decisionmaking, on the euro and on monetary policy in general, the euro currency would hit a mortal crisis and fail, and monetary union would collapse. EU Survivor