The Rocky Road to Globalization

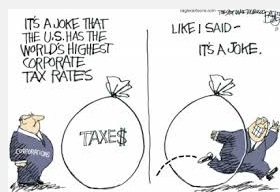

President Barack Obama said last September that he would get tough on companies that avoid tax through “inversions”—merging with or buying foreign firms so as to shift their domicile abroad—some wondered if this would end a wave of corporate emigration. Some high-profile deals were called off, but other companies have continued to tiptoe out of America to places where the taxman is kinder and has shorter arms.

For many firms, staying in America is just too costly. Take Burger King, a fast-food chain, which last year shifted domicile to Canada after merging with Tim Horton’s, a coffee-shop operator there. Before the move, it would have had to pay up to 39% tax on foreign earnings when it brought them into America. Now that it is Canadian, it pays 39% only on profits earned in America, about 26% on Canadian profits and the (often lower) local rate elsewhere.

Inversions can cause a domino effect within industries, as the first companies to emigrate to a low-tax country gain an advantage that prompts rivals to follow suit. The logical way to stem the tide would be to bring America’s tax laws in line with international norms. Britain, Germany and Japan all have lower corporate rates and are among the majority of countries that tax firms only on profits earned on their territory. But the likelihood of a substantial tax reform in America is low—vanishingly so before 2017.

So, rather than making it nicer for companies to stay, the US Treasury has been trying to make it harder for them to leave. There has long been a rule whereby any inversion resulting in the American firm’s shareholders owning 80% of the merged group would be taxed as if it were still American. In September, loopholes in this rule were closed

AbbVie, a drug company, blamed these stricter rules when it abandoned plans to merge with Shire of Ireland. Walgreens, a pharmacy chain, insisted it also had other reasons for dropping a plan to move to Europe, though its patriotic decision to stay American earned it some good publicity.

Despite such speed bumps, inversions still make enormous sense for companies with large overseas operations. If anything, the rule changes have led to more companies looking to get out before it is too late.

Emigrating from Deerfield, Illinois to London, as in CF Industries’ case, or from Minnesota to Dublin, as in Medtronic’s, isn’t as dramatic as it seems. These tend to be mainly paper moves. “Here in the Netherlands you don’t even need a chimney to be domiciled,” says Indra Romgens, a corporate researcher, of the country’s many brass-plate headquarters. But the tides are slowly turning, as low-tax countries are beginning to require relocating companies to have a more substantial presence.

Now stricter anti-inversion rules make it harder for American firms to pursue de facto takeovers of foreign rivals, they are becoming the prey rather than the predators. If the American authorities succeeded in stopping inversions, all that would happen is that foreign takeovers of American firms would accelerate.