William D. Cohan writes: On May 27, in her first major prosecutorial act as the new U.S. attorney general, Loretta Lynch unsealed a 47-count indictment against nine FIFA officials and another five corporate executives. She was passionate about their wrongdoing.

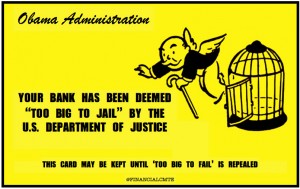

Lost in the hoopla surrounding the event was a depressing fact. Lynch and her predecessor, Eric Holder, appear to have turned the page on a more relevant vein of wrongdoing: the profligate and dishonest behavior of Wall Street bankers, traders, and executives in the years leading up to the 2008 financial crisis. How we arrived at a place where Wall Street misdeeds go virtually unpunished while soccer executives in Switzerland get arrested is murky at best.

Since 2009, 49 financial institutions have paid various government entities and private plaintiffs nearly $190 billion in fines and settlements, according to an analysis by the investment bank Keefe, Bruyette & Woods. That may seem like a big number, but the money has come from shareholders, not individual bankers. In early 2014, just weeks after Jamie Dimon, the CEO of JPMorgan Chase, settled out of court with the Justice Department, the bank’s board of directors gave him a 74 percent raise, bringing his salary to $20 million.

After the savings-and-loan crisis of the 1980s, more than 1,000 bankers were jailed.

The more meaningful number is how many Wall Street executives have gone to jail for playing a part in the crisis. That number is one. (Kareem Serageldin, a senior trader at Credit Suisse, is serving a 30-month sentence for inflating the value of mortgage bonds in his trading portfolio, allowing them to appear more valuable than they really were.)

Do:Wall Street bankers make it their daily business to figure out ways to abide by the letter of the law while violating its spirit. Much of the behavior that led to the crisis involved recklessness and poor judgment, not fraud.

Any narrative of how we got to this point has to start with the so-called Holder Doctrine, a June 1999 memorandum written by the then–deputy attorney general warning of the dangers of prosecuting big banks—a variant of the “too big to fail” argument that has since become so familiar.

A serious national investigation of the practices of Wall Street’s pre-crash mortgage-banking activities did not begin in earnest until mid-2012—at least five years after the worst of the bad behavior had occurred—following President Obama’s call to action in the State of the Union address that January and the issuance of subpoenas to Wall Street’s biggest banks. The five-year statute of limitations for ordinary criminal fraud charges had passed while the Justice Department dithered, but civil prosecution of banks and individual bankers, which has a 10-year statute of limitations under a particular banking law, was still a possibility. Holder gave his various U.S. attorneys around the country responsibility for investigating.

In November 2013, as part of a deal that kept Wagner’s complaint from becoming public—and the specifics of Fleischmann’s revelations from being widely disseminated—JPMorgan Chase agreed to a $13 billion settlement with various federal and state agencies, then the largest of its kind. Holder heralded the settlement as an important moment of accountability for Wall Street. But extracting large settlements paid with shareholders’ money is not the same as bringing alleged wrongdoers to justice.

The Justice Department reached agreements with other Wall Street banks, among them Citigroup and Bank of America, using a similar playbook.

In February, shortly before Lynch succeeded him, Holder gave federal attorneys and their staffs a deadline: they had 90 days to bring any new prosecutions against individual bankers, traders, or executives on Wall Street before probes against them would be closed. That deadline came and went in May.