Nick Timiraos writes: With the Puerto Rican economy in decline, Luis Acevedo, a 31-year-old chemist, decided to get a degree in chemical engineering to give him a better chance at boosting his earnings. Even with the degree, he has had no luck finding a job after five months, and he said competition is fierce given a high unemployment rate, about 12%. “The way things are going I’m starting to apply abroad,” Mr. Acevedo said.

Weak job prospects have prompted Puerto Ricans, who are U.S. citizens, to seek employment in places like Florida, New York and New Jersey. Since 2000, total employment is down 11% in Puerto Rico, while it is 7% higher in the U.S. The island was projected to post one of the largest population declines in the world last year, according to U.S. government figures.

More than 27% of Puerto Ricans between 15 and 24 years old who were in the labor force were unemployed in 2013, compared to nearly 16% in the U.S.

Andrew Bary of Barron’s tells Jack Otter what just happened in San Juan, and what it means for municipal bond investors.

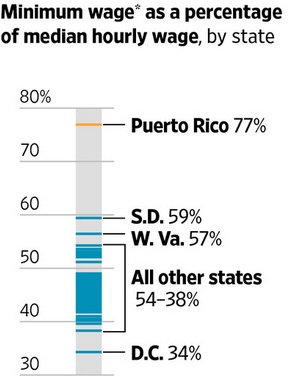

Labor unions on the mainland pushed for the federal minimum wage to cover Puerto Rico in the 1970s amid concerns that the island would create low-wage competition for mainland jobs. The move eliminated a comparative economic advantage for the island, while tax breaks designed to lure multinationals did little to establish permanent job growth, said Barry Bosworth, an economist at the Brookings Institution in Washington.

Congress mandated two U.S. territories in the Pacific, American Samoa and the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands, to increase their minimum wages in 2007 by 50 cents annually until meeting the federal level this year, but it delayed those increases in 2010 amid concerns about economic growth.

“They are begging the government to stop the onwards march of raising the minimum wage,” said Mr. Porzecanski. “It’s better to be hired at $5 than not to be hired at $7.25.” Minimum wages in American Samoa, which range from $4.18 to $4.76 an hour, are set to rise by 50 cents at the end of September.

Labor dynamics are only part of the problem with Puerto Rico’s economy, which also faces poor business investment, high tax evasion, and unusually expensive electricity and other costs of living.

The Jones Act, a law that requires most shipping between U.S. ports to rely on a small and specific fleet of U.S.-flagged vessels, means that just a handful of ships serve Puerto Rico, limiting competition and increasing costs of basic goods. The Krueger Report recommends that Congress exempt Puerto Rico from the Jones Act, following similar exemptions for the U.S. Virgin Islands.

In Puerto Rico, broad use of government benefit programs have further damped workforce participation. Transfer payments, such as food stamps and disability benefits, account for roughly 40% of personal income in Puerto Rico, double the share on the U.S. mainland, according to the New York Fed.

Those payments tend to be generous relative to local incomes because payments are indexed to conditions on the mainland. Moreover, because they decline as wages rise, they can create a disincentive to work. The Krueger report recommends providing lower benefit payments to a larger number of people, which would maintain the social safety net while encouraging more labor-force participation.

At the same time, economists say other local labor laws, including more generous overtime pay and vacation rules, plus laws that make it harder to fire workers, have made employers reluctant to hire.

While it would make sense to exempt Puerto Rico from future increases in the federal minimum wage, cutting wages “will just accelerate the exit from the island,” Mr. Bosworth said. “The fundamental problem in Puerto Rico is the lack of jobs.