Joseph E. Stiglitz and Martin Guzman write: Governments sometimes need to restructure their debts. Otherwise, a country’s economic and political stability may be threatened. But, in the absence of an international rule of law for resolving sovereign defaults, the world pays a higher price than it should for such restructurings. The result is a poorly functioning sovereign-debt market, marked by unnecessary strife and costly delays in addressing problems when they arise.

So the question of how to manage sovereign-debt restructuring – to reduce debt to levels that are sustainable – is more pressing than ever. The current system puts excessive faith in the “virtues” of markets. Disputes are generally resolved not on the basis of rules that ensure fair resolution, but by bargaining among unequals, with the rich and powerful usually imposing their will on others. The resulting outcomes are generally not only inequitable, but also inefficient.

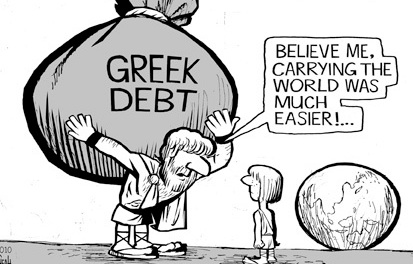

Greece’s debt restructuring in 2012 is a case in point. Excessive penalties lead to negative-sum games, in which the debtor cannot recover and creditors do not benefit from the larger repayment capacity that recovery would entail.

The absence of a rule of law for debt restructuring delays fresh starts and can lead to chaos. Sovereign-debt restructurings are even more complicated than domestic bankruptcy, plagued as they are by problems of multiple jurisdictions, implicit as well as explicit claimants, and ill-defined assets upon which claimants can draw.

A new framework should include clauses providing for stays of litigation while the restructuring is being carried out. It should also contain provisions for lending into arrears: lenders willing to provide credit to a country going through a restructuring would receive priority treatment. Such lenders would thus have an incentive to provide fresh resources to countries when they need them the most.

There should be agreement, too, that no country can sign away its basic rights. T

This is particularly important because of the tendency of financial markets to induce short-sighted politicians to loosen today’s budget constraints, or to lend to flagrantly corrupt governments such as the fallen Yanukovych regime in Ukraine, at the expense of future generations.

This means that regulation of sovereign-debt restructuring cannot be based at the International Monetary Fund, which is too closely affiliated with creditors (and is a creditor itself). To minimize the potential for conflicts of interest, the framework could be implemented by the United Nations.

The crisis in Europe is just the latest example of the high costs – for creditors and debtors alike – entailed by the absence of an international rule of law for resolving sovereign-debt crises.