James Galbraith writes: The International Monetary Fund’s chief economist, Olivier Blanchard, recently asked a simple and important question: “How much of an adjustment has to be made by Greece, how much has to be made by its official creditors?” But that raises two more questions: How much of an adjustment has Greece already made? And have its creditors given anything at all?

The IMF initially projected that Greece’s real (inflation-adjusted) GDP would contract by around 5% over the 2010-2011 period, stabilize in 2012, and grow thereafter. In fact, real GDP fell 25%, and did not recover. And, because nominal GDP fell in 2014 and continues to fall, the debt/GDP ratio, which was supposed to stabilize three years ago, continues to rise.

Greece agreed “to generate enough of a primary surplus to limit its indebtedness” and to implement “a number of reforms which should lead to higher growth.” Those so-called reforms included sharply lower public spending, minimum-wage reductions, fire-sale privatizations, an end to collective bargaining, and deep pension cuts. Greece followed through, but the depression continued.

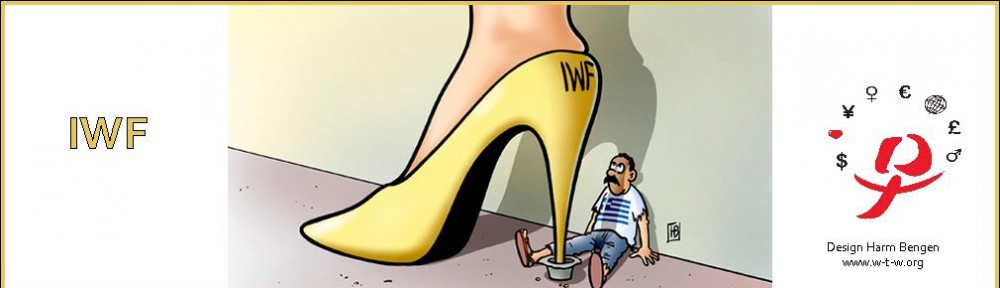

The IMF and Greece’s other creditors have assumed that massive fiscal contraction has only a temporary effect on economic activity, employment, and taxes, and that slashing wages, pensions, and public jobs has a magical effect on growth. This has proved false. Indeed, Greece’s post-2010 adjustment led to economic disaster – and the IMF’s worst predictive failure ever.

Blanchard should know better than to persist with this fiasco. Once the link between “reform” and growth is broken – as it has been in Greece – his argument collapses.

Apart from pensions and wages, spending has already been “cut to the bone.” And remember: the effect of this approach on growth was negative. So, in defiance of overwhelming evidence, the IMF now wants to target the remaining sector, pensions, where massive cuts – more than 40% in many cases – have already been made. The new cuts being demanded would hit the poor very hard.

Pension payments now account for 16% of Greek GDP precisely because Greece’s economy is 25% smaller than it was in 2009.

To get pensions down by one percentage point of GDP, nominal economic growth of just 4% per year for two years would suffice – with no further cuts. Why not have “credible measures” to achieve that goal?

This brings us to Greek debt. As everyone at the IMF knows, a debt overhang is a vast unfunded tax liability.

Greece’s debt has not been sustainable at any point during the last five years, and that it is not sustainable now. On this point, Greece and the IMF agree.

In fact, Greece has a credible debt proposal. First, let the European Stabilization Mechanism (ESM) lend €27 billion ($30 billion), at long maturities, to retire the Greek bonds that the European Central Bank foolishly bought in 2010. Second, use the profits on those bonds to pay off the IMF. Third, include Greece in the ECB’s program of quantitative easing, which would let it return to the markets.

Now it is the IMF’s turn, beginning with the decision to admit that the policies it has imposed for five long years created a disaster. For the other creditors, the toughest choice is to admit – as the IMF knows – that their Greek debts must be restructured. New loans for failed policies – the current joint creditor proposal – is, for them, no adjustment at all.