There are several reasons the “quick and dirty” approach has been the norm for Greece’s interactions with its European partner governments, European institutions and the International Monetary Fund (IMF). And the results have not been all bad.

This piecemeal muddle-through approach had the potential to buy time for Greece and the euro zone to pivot from the urgency of crisis management to thoughtful crisis resolution and effective crisis prevention. It allowed both sides to pursue the type of (internal and regional) political consensus and compromises needed for a comprehensive solution.

It also bought time for all sides to erect the internal defences that would be required if the hopes for a positive outcome gave way to the pressing reality of a more disorderly resolution, such as a forced Greek exit from the euro.

But too little was achieved during this transition period, and it has proved a costly bridge to nowhere.

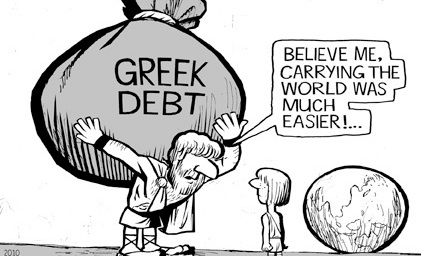

A significant amount of potentially unpayable Greek debt has been transferred from private creditors to public balance sheets underpinned by European taxpayers. Many of these private entities had been paid handsomely for their willingness to take on the sovereign credit risk of Greece and, thanks to generous bailout funding from the official sector, quite a few have been able to exit without much cost.

Failing to see much sustainable improvement, Greek citizens have been pulling their cash out of banks. This has contributed to wider capital flight that sucks operating oxygen out of the country’s economy and puts a growing number of institutions at risk of bankruptcy.

Greece’s deep and persistent economic problems have caused significant human distress and worsened the structural impairments to future economic recovery and prosperity.

Negotiating tensions between Greece and its creditors have been compounded by co-ordination difficulties among the creditor group itself (what used to be called the Troika: the European Central Bank, European Union and IMF).

The cost-benefit calculation of the “quick and dirty” approach has become less favourable and now approaches acute levels. Yes, official creditors such as the ECB and IMF are under even greater pressure to make new loans to Greece if they hope to be repaid their prior loans.

But such financial engineering no longer fools anyone.

Lagarde’s plea for a comprehensive approach reflects a growing urgency as the inefficiency and cost of the successive Band-Aids have become clear. Yet with the odds favouring another muddle-through or – as is increasingly likely – a messy Graccident, she faces a considerable challenge.