On the Rocky Road to Globalization

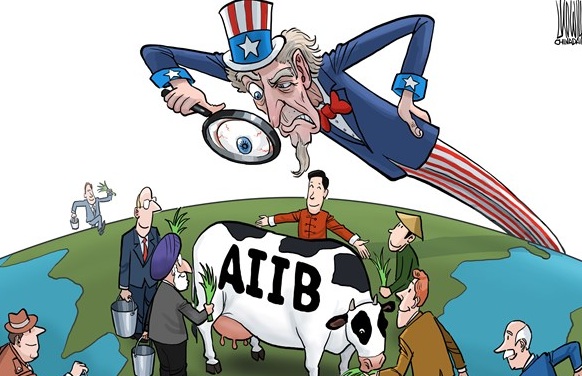

Anne-Marie Slaughter writes: China’s success in establishing the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank has been widely regarded as a diplomatic fiasco for the United States. After discouraging all US allies from joining the AIIB, President Barack Obama’s administration watched as Great Britain led a raft of Western European countries, followed by Australia and South Korea, into doing just that.

Worse, the Obama administration found itself in the position of trying to block Chinese efforts to create a regional financial institution after the US itself was unable to deliver on promises to give China and other major emerging economies a greater say in the governance of the International Monetary Fund.

China will control half of the voting shares in the AIIB, initially capitalized at $1 billion. Unless the Western victors of World War II can update the rules and institutions that underpinned the post-war international order, they will find themselves in a world with multiple competing regional orders and even dueling multilateral institutions.

From the point of view of developing countries in need of capital, competing banks probably look like a good thing. But what about the impact on actual development, the likelihood that individual citizens of poor countries will live richer, healthier, more educated lives? World Bank conditionality often includes provisions on human rights and environmental protections that make it more difficult for governments bent on growth at any cost to run roughshod over their people. Competition is good, but unregulated competition typically ends up in a race to the bottom.

China’s establishment of the AIIB is the latest sign of a broader move away from the view that aid to developing countries is best provided in the form of massive government-to-government transfers. Power and wealth are not only diffusing across the international system, but also within states.

The new model of development may be one based on the recognition “that the United States is one of many actors, and that countries require investments from multiple sources to achieve sustained and inclusive economic growth.” Initiatives such as Feed the Future, the US Global Development Lab, and Power Africa combine “local ownership, private investment, innovation, multi-stakeholder partnerships, and mutual accountability.”

This new model moves beyond the mantra of “public-private partnership.” It genuinely leverages multiple sources of money and expertise in broad coalitions pursuing the same big goal.

Power Africa takes a “transaction-centered approach,” creating teams to align incentives among “host governments, the private sector, and donors.” Unlike big government-to-government transfers, which can often end up in the pockets of officials, the point is to ensure that deals actually get done and investments flow to their intended destination.

Skeptics will say that the US is simply making a virtue of necessity. The federal government no longer has billions of dollars to dole out to foreign governments, while China is far more centralized and less beholden to its taxpayers.

That criticism contains some truth. But, over the longer term, the new US model of development is actually far more resilient and sustainable than the old government-to-government model. Only societies with thriving sectors free of government control can participate in these broad coalitions of public, private, and civic actors.

Overall, the AIIB is a positive development. More money aimed at helping poor countries become middle-income countries and at middle-income countries to help them provide transport, energy, and communication for their people is a good thing. But the Asian way is not the only way.