Lawrence Summers writes: This past month may be remembered as the moment the United States lost its role as the underwriter of the global economic system. I can think of no event since Bretton Woods comparable to the combination of China’s effort to establish a major new institution and the failure of the United States to persuade dozens of its traditional allies, starting with Britain, to stay out. This should lead to a comprehensive review of the U.S. approach to global economics.

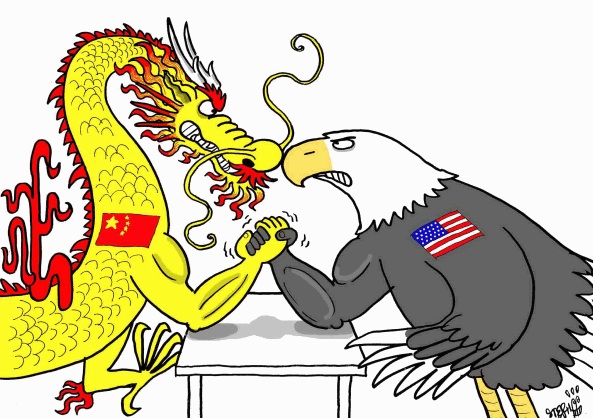

With China’s economic size rivaling that of the United States and emerging markets accounting for at least half of world output, the global economic architecture needs substantial adjustment. Political pressures from all sides in the United States have rendered the architecture increasingly dysfunctional.

Largely because of resistance from the right, the United States stands alone in the world in failing to approve International Monetary Fund governance reforms that Washington itself pushed for in 2009. At the same time, pressures from the left have led to pervasive restrictions on the infrastructure projects financed through the existing development banks — which consequently have receded as infrastructure funders, even as many developing countries have come to see infrastructure finance as their principal external funding need.

With U.S. commitments unhonored and U.S.-backed policies blocking the kinds of finance other countries want

First, U.S. leadership must have a bipartisan foundation, be free from gross hypocrisy and be restrained in the pursuit of our self-interest.

Other countries are legitimately frustrated when U.S. officials ask them to adjust their policies — only to then insist that state-level regulators, independent agencies and far-reaching judicial actions are beyond their control.

Second, in global as well as domestic politics, the middle class counts the most. It sometimes seems that the prevailing global agenda combines elite concerns about matters such as intellectual property, investment protection and regulatory harmonization with moral concerns about global poverty and posterity while offering little that speaks to those in the middle.

Third, we may be headed into a world where capital is abundant, deflationary pressures are substantial and demand could be in short supply for quite some time. In no big industrialized country do markets expect real interest rates to be much above zero in 2020 or for inflation targets to be achieved.

These precepts are just a beginning. There are questions about global public goods, about acting with the speed and clarity that the current era requires, about cooperation between governmental and nongovernmental actors and much more. What is crucial is that the events of the past month will be seen by future historians not as the end of an era, but as a salutary wake-up call.